|

Welcome to the Yocto Project! The Yocto Project is an open-source collaboration project focused on embedded Linux developers. Among other things, the Yocto Project uses a build system based on the Poky project to construct complete Linux images. The Poky project, in turn, draws from and contributes back to the OpenEmbedded project.

If you don't have a system that runs Linux and you want to give the Yocto Project a test run, you might consider using the Yocto Project Build Appliance. The Build Appliance allows you to build and boot a custom embedded Linux image with the Yocto Project using a non-Linux development system. See the Yocto Project Build Appliance for more information.

On the other hand, if you know all about open-source development, Linux development environments, Git source repositories and the like and you just want some quick information that lets you try out the Yocto Project on your Linux system, skip right to the "Super User" section at the end of this quick start.

For the rest of you, this short document will give you some basic information about the environment and let you experience it in its simplest form. After reading this document, you will have a basic understanding of what the Yocto Project is and how to use some of its core components. This document steps you through a simple example showing you how to build a small image and run it using the Quick EMUlator (QEMU emulator).

For more detailed information on the Yocto Project, you should check out these resources:

Website: The Yocto Project Website provides the latest builds, breaking news, full development documentation, and a rich Yocto Project Development Community into which you can tap.

FAQs: Lists commonly asked Yocto Project questions and answers. You can find two FAQs: Yocto Project FAQ on a wiki, and the "FAQ" chapter in the Yocto Project Reference Manual.

Developer Screencast: The Getting Started with the Yocto Project - New Developer Screencast Tutorial provides a 30-minute video for the user new to the Yocto Project but familiar with Linux build systems.

Manual Notes

This version of the Yocto Project Quick Start is for the 1.3.2 release of the Yocto Project. To be sure you have the latest version of the manual for this release, go to the Yocto Project documentation page and select the manual from that site. Manuals from the site are more up-to-date than manuals derived from the Yocto Project released TAR files.

If you located this manual through a web search, the version of the manual might not be the one you want (e.g. the search might have returned a manual much older than the Yocto Project version with which you are working). You can see all Yocto Project major releases by visiting the Releases page. If you need a version of this manual for a different Yocto Project release, visit the Yocto Project documentation page and select the manual set by using the "ACTIVE RELEASES DOCUMENTATION" or "DOCUMENTS ARCHIVE" pull-down menus.

To report any inaccuracies or problems with this manual, send an email to the Yocto Project discussion group at

yocto@yoctoproject.comor log into the freenode#yoctochannel.

The Yocto Project through the OpenEmbedded build system provides an open source development environment targeting the ARM, MIPS, PowerPC and x86 architectures for a variety of platforms including x86-64 and emulated ones. You can use components from the Yocto Project to design, develop, build, debug, simulate, and test the complete software stack using Linux, the X Window System, GNOME Mobile-based application frameworks, and Qt frameworks.

|

The Yocto Project Development Environment

Here are some highlights for the Yocto Project:

Provides a recent Linux kernel along with a set of system commands and libraries suitable for the embedded environment.

Makes available system components such as X11, GTK+, Qt, Clutter, and SDL (among others) so you can create a rich user experience on devices that have display hardware. For devices that don't have a display or where you wish to use alternative UI frameworks, these components need not be installed.

Creates a focused and stable core compatible with the OpenEmbedded project with which you can easily and reliably build and develop.

Fully supports a wide range of hardware and device emulation through the QEMU Emulator.

The Yocto Project can generate images for many kinds of devices. However, the standard example machines target QEMU full-system emulation for x86, x86-64, ARM, MIPS, and PPC-based architectures as well as specific hardware such as the Intel® Desktop Board DH55TC. Because an image developed with the Yocto Project can boot inside a QEMU emulator, the development environment works nicely as a test platform for developing embedded software.

Another important Yocto Project feature is the Sato reference User Interface. This optional GNOME mobile-based UI, which is intended for devices with restricted screen sizes, sits neatly on top of a device using the GNOME Mobile Stack and provides a well-defined user experience. Implemented in its own layer, it makes it clear to developers how they can implement their own user interface on top of a Linux image created with the Yocto Project.

You need these things to develop in the Yocto Project environment:

A host system running a supported Linux distribution (i.e. recent releases of Fedora, openSUSE, CentOS, and Ubuntu). If the host system supports multiple cores and threads, you can configure the Yocto Project build system to decrease the time needed to build images significantly.

The right packages.

A release of the Yocto Project.

The Yocto Project team is continually verifying more and more Linux distributions with each release. In general, if you have the current release minus one of the following distributions you should have no problems.

Ubuntu

Fedora

openSUSE

CentOS

For a more detailed list of distributions that support the Yocto Project, see the "Supported Linux Distributions" section in the Yocto Project Reference Manual.

Note

For notes about using the Yocto Project on a RHEL 4-based host, see the BuildingOnRHEL4 wiki page.

The OpenEmbedded build system should be able to run on any modern distribution with Python 2.6 or 2.7. Earlier releases of Python are known to not work and the system does not support Python 3 at this time. This document assumes you are running one of the previously noted distributions on your Linux-based host systems.

Note

If you attempt to use a distribution not in the above list, you may or may not have success - you are venturing into untested territory. Refer to OE and Your Distro and Required Software for information for other distributions used with the OpenEmbedded project, which might be a starting point for exploration. If you go down this path, you should expect problems. When you do, please go to Yocto Project Bugzilla and submit a bug. We are interested in hearing about your experience.

Packages and package installation vary depending on your development system and on your intent. For example, if you want to build an image that can run on QEMU in graphical mode (a minimal, basic build requirement), then the number of packages is different than if you want to build an image on a headless system or build out the Yocto Project documentation set. Collectively, the number of required packages is large if you want to be able to cover all cases.

Note

In general, you need to have root access and then install the required packages. Thus, the commands in the following section may or may not work depending on whether or not your Linux distribution hassudo installed.

The next few sections list, by supported Linux Distributions, the required packages needed to build an image that runs on QEMU in graphical mode (e.g. essential plus graphics support).

For lists of required packages for other scenarios, see the "Required Packages for the Host Development System" section in the Yocto Project Reference Manual.

The essential packages you need for a supported Ubuntu distribution are shown in the following command:

$ sudo apt-get install gawk wget git-core diffstat unzip texinfo build-essential chrpath libsdl1.2-dev xterm

The essential packages you need for a supported Fedora distribution are shown in the following command:

$ sudo yum install gawk make wget tar bzip2 gzip python unzip perl patch diffutils diffstat git

cpp gcc gcc-c++ eglibc-devel texinfo chrpath ccache SDL-devel xterm

The essential packages you need for a supported openSUSE distribution are shown in the following command:

$ sudo zypper install python gcc gcc-c++ git chrpath make wget diffstat texinfo python-curses libSDL-devel xterm

The essential packages you need for a supported CentOS distribution are shown in the following command:

$ sudo yum -y install gawk make wget tar bzip2 gzip python unzip perl patch diffutils diffstat git

cpp gcc gcc-c++ glibc-devel texinfo chrpath SDL-devel xterm

Note

Depending on the CentOS version you are using, other requirements and dependencies might exist. For details, you should look at the CentOS sections on the Poky/GettingStarted/Dependencies wiki page.

You can download the latest Yocto Project release by going to the Yocto Project Download page. Just go to the page and click the "Yocto Downloads" link found in the "Download" navigation pane to the right to view all available Yocto Project releases. Then, click the "Yocto Release" link for the release you want from the list to begin the download. Nightly and developmental builds are also maintained at http://autobuilder.yoctoproject.org/nightly/. However, for this document a released version of Yocto Project is used.

You can also get the Yocto Project files you need by setting up (cloning in Git terms)

a local copy of the poky Git repository on your host development

system.

Doing so allows you to contribute back to the Yocto Project project.

For information on how to get set up using this method, see the

"Yocto

Project Release" item in the Yocto Project Development Manual.

Now that you have your system requirements in order, you can give the Yocto Project a try. This section presents some steps that let you do the following:

Build an image and run it in the QEMU emulator

Use a pre-built image and run it in the QEMU emulator

In the development environment you will need to build an image whenever you change hardware support, add or change system libraries, or add or change services that have dependencies.

Building an Image

Use the following commands to build your image. The OpenEmbedded build process creates an entire Linux distribution, including the toolchain, from source.

Note

The build process using Sato currently consumes about 50GB of disk space. To allow for variations in the build process and for future package expansion, we recommend having at least 100GB of free disk space.

Note

By default, the build process searches for source code using a pre-determined order through a set of locations. If you encounter problems with the build process finding and downloading source code, see the "How does the OpenEmbedded build system obtain source code and will it work behind my firewall or proxy server?" in the Yocto Project Reference Manual.

$ wget http://downloads.yoctoproject.org/releases/yocto/yocto-1.3.2/poky-danny-8.0.2.tar.bz2

$ tar xjf poky-danny-8.0.2.tar.bz2

$ cd poky-danny-8.0.2

$ source oe-init-build-env

Tip

To help conserve disk space during builds, you can add the following statement

to your project's configuration file, which for this example

is poky-danny-8.0.2-build/conf/local.conf.

Adding this statement deletes the work directory used for building a package

once the package is built.

INHERIT += "rm_work"

In the previous example, the first command retrieves the Yocto Project release tarball from the source repositories using the

wgetcommand. Alternatively, you can go to the Yocto Project website's Downloads page to retrieve the tarball.The second command extracts the files from the tarball and places them into a directory named

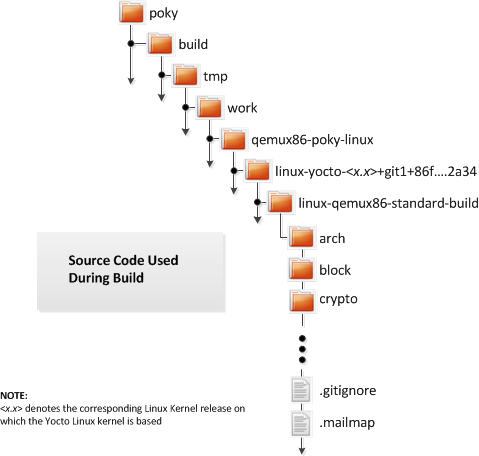

poky-danny-8.0.2in the current directory.The third and fourth commands change the working directory to the Source Directory and run the Yocto Project environment setup script. Running this script defines OpenEmbedded build environment settings needed to complete the build. The script also creates the Build Directory, which is

buildin this case and is located in the Source Directory. After the script runs, your current working directory is set to the Build Directory. Later, when the build completes, the Build Directory contains all the files created during the build.

Take some time to examine your local.conf file

in your project's configuration directory, which is found in the Build Directory.

The defaults in that file should work fine.

However, there are some variables of interest at which you might look.

By default, the target architecture for the build is qemux86,

which produces an image that can be used in the QEMU emulator and is targeted at an

Intel® 32-bit based architecture.

To change this default, edit the value of the MACHINE variable

in the configuration file before launching the build.

Another couple of variables of interest are the

BB_NUMBER_THREADS and the

PARALLEL_MAKE variables.

By default, these variables are commented out.

However, if you have a multi-core CPU you might want to uncomment

the lines and set both variables equal to twice the number of your

host's processor cores.

Setting these variables can significantly shorten your build time.

Another consideration before you build is the package manager used when creating

the image.

By default, the OpenEmbedded build system uses the RPM package manager.

You can control this configuration by using the

PACKAGE_CLASSESpackage*.bbclass"

in the Yocto Project Reference Manual.

Continue with the following command to build an OS image for the target, which is

core-image-sato in this example.

For information on the -k option use the

bitbake --help command or see the

"BitBake" section in

the Yocto Project Reference Manual.

$ bitbake -k core-image-sato

Note

BitBake requires Python 2.6 or 2.7. For more information on this requirement, see the FAQ in the Yocto Project Reference Manual.

The final command runs the image:

$ runqemu qemux86

Note

Depending on the number of processors and cores, the amount or RAM, the speed of your Internet connection and other factors, the build process could take several hours the first time you run it. Subsequent builds run much faster since parts of the build are cached.

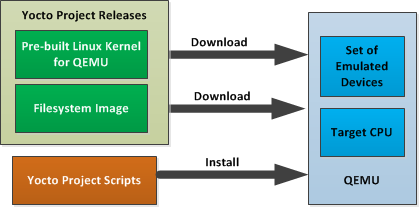

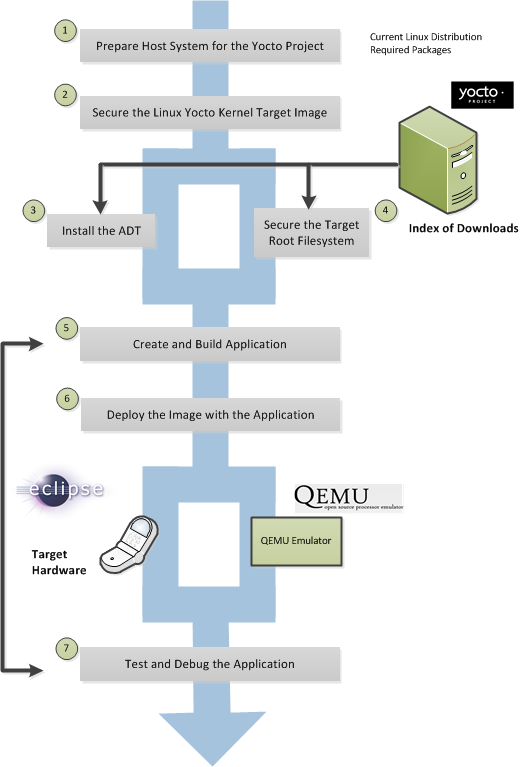

If hardware, libraries and services are stable, you can get started by using a pre-built binary of the filesystem image, kernel, and toolchain and run it using the QEMU emulator. This scenario is useful for developing application software.

Using a Pre-Built Image

For this scenario, you need to do several things:

Install the appropriate stand-alone toolchain tarball.

Download the pre-built image that will boot with QEMU. You need to be sure to get the QEMU image that matches your target machine’s architecture (e.g. x86, ARM, etc.).

Download the filesystem image for your target machine's architecture.

Set up the environment to emulate the hardware and then start the QEMU emulator.

You can download a tarball installer, which includes the pre-built toolchain, the

runqemu

script, and support files from the appropriate directory under

http://downloads.yoctoproject.org/releases/yocto/yocto-1.3.2/toolchain/.

Toolchains are available for 32-bit and 64-bit development systems from the

i686 and x86-64 directories, respectively.

Each type of development system supports five target architectures.

The names of the tarball installer scripts are such that a string representing the

host system appears first in the filename and then is immediately followed by a

string representing the target architecture.

poky-eglibc-<host_system>-<arch>-toolchain-gmae-<release>.sh

Where:

<host_system> is a string representing your development system:

i686 or x86_64.

<arch> is a string representing the target architecture:

i586, x86_64, powerpc, mips, or arm.

<release> is the version of Yocto Project.

For example, the following toolchain installer is for a 64-bit development host system and a 32-bit target architecture:

poky-eglibc-x86_64-i586-toolchain-gmae-1.3.2.sh

Toolchains are self-contained and by default are installed into /opt/poky.

However, when you run the toolchain installer, you can choose an installation directory.

The following command shows how to run the installer given a toolchain tarball for a 64-bit development host system and a 32-bit target architecture. You must change the permissions on the toolchain installer script so that it is executable.

The example assumes the toolchain installer is located in ~/Downloads/.

Note

If you do not have write permissions for the directory into which you are installing the toolchain, the toolchain installer notifies you and exits. Be sure you have write permissions in the directory and run the installer again.

$ ~/Downloads/poky-eglibc-x86_64-i586-toolchain-gmae-1.3.2.sh

For more information on how to install tarballs, see the "Using a Cross-Toolchain Tarball" and "Using BitBake and the Build Directory" sections in the Yocto Project Application Developer's Guide.

You can download the pre-built Linux kernel suitable for running in the QEMU emulator from

http://downloads.yoctoproject.org/releases/yocto/yocto-1.3.2/machines/qemu.

Be sure to use the kernel that matches the architecture you want to simulate.

Download areas exist for the five supported machine architectures:

qemuarm, qemumips, qemuppc,

qemux86, and qemux86-64.

Most kernel files have one of the following forms:

*zImage-qemu<arch>.bin

vmlinux-qemu<arch>.bin

Where:

<arch> is a string representing the target architecture:

x86, x86-64, ppc, mips, or arm.

You can learn more about downloading a Yocto Project kernel in the "Yocto Project Kernel" bulleted item in the Yocto Project Development Manual.

You can also download the filesystem image suitable for your target architecture from http://downloads.yoctoproject.org/releases/yocto/yocto-1.3.2/machines/qemu. Again, be sure to use the filesystem that matches the architecture you want to simulate.

The filesystem image has two tarball forms: ext3 and

tar.

You must use the ext3 form when booting an image using the

QEMU emulator.

The tar form can be flattened out in your host development system

and used for build purposes with the Yocto Project.

core-image-<profile>-qemu<arch>.ext3

core-image-<profile>-qemu<arch>.tar.bz2

Where:

<profile> is the filesystem image's profile:

lsb, lsb-dev, lsb-sdk, lsb-qt3, minimal, minimal-dev, sato, sato-dev, or sato-sdk.

For information on these types of image profiles, see the

"Images" chapter

in the Yocto Project Reference Manual.

<arch> is a string representing the target architecture:

x86, x86-64, ppc, mips, or arm.

Before you start the QEMU emulator, you need to set up the emulation environment. The following command form sets up the emulation environment.

$ source /opt/poky/1.3.2/environment-setup-<arch>-poky-linux-<if>

Where:

<arch> is a string representing the target architecture:

i586, x86_64, ppc603e, mips, or armv5te.

<if> is a string representing an embedded application binary interface.

Not all setup scripts include this string.

Finally, this command form invokes the QEMU emulator

$ runqemu <qemuarch> <kernel-image> <filesystem-image>

Where:

<qemuarch> is a string representing the target architecture: qemux86, qemux86-64,

qemuppc, qemumips, or qemuarm.

<kernel-image> is the architecture-specific kernel image.

<filesystem-image> is the .ext3 filesystem image.

Continuing with the example, the following two commands setup the emulation

environment and launch QEMU.

This example assumes the root filesystem (.ext3 file) and

the pre-built kernel image file both reside in your home directory.

The kernel and filesystem are for a 32-bit target architecture.

$ cd $HOME

$ source /opt/poky/1.3.2/environment-setup-i586-poky-linux

$ runqemu qemux86 bzImage-qemux86.bin \

core-image-sato-qemux86.ext3

The environment in which QEMU launches varies depending on the filesystem image and on the target architecture. For example, if you source the environment for the ARM target architecture and then boot the minimal QEMU image, the emulator comes up in a new shell in command-line mode. However, if you boot the SDK image, QEMU comes up with a GUI.

Note

Booting the PPC image results in QEMU launching in the same shell in command-line mode.

This section [1] gives you a minimal description of how to use the Yocto Project to build images for a BeagleBoard xM starting from scratch. The steps were performed on a 64-bit Ubuntu 10.04 system.

Set up your Source Directory one of two ways:

Tarball: Use if you want the latest stable release:

$ wget http://downloads.yoctoproject.org/releases/yocto/yocto-1.3.2/poky-danny-8.0.2.tar.bz2 $ tar xvjf poky-danny-8.0.2.tar.bz2Git Repository: Use if you want to work with cutting edge development content:

$ git clone git://git.yoctoproject.org/poky

The remainder of the section assumes the Git repository method.

You need some packages for everything to work. Rather than duplicate them here, look at the "The Packages" section earlier in this quick start.

From the parent directory your Source Directory, initialize your environment and provide a meaningful Build Directory name:

$ source poky/oe-init-build-env mybuilds

At this point, the mybuilds directory has been created for you

and it is now your current working directory.

If you don't provide your own directory name it defaults to build,

which is inside the Source Directory.

Initializing the build environment creates a conf/local.conf configuration file

in the Build Directory.

You need to manually edit this file to specify the machine you are building and to optimize

your build time.

Here are the minimal changes to make:

BB_NUMBER_THREADS = "8"

PARALLEL_MAKE = "-j 8"

MACHINE ?= "beagleboard"

Briefly, set BB_NUMBER_THREADS

and PARALLEL_MAKE to

twice your host processor's number of cores.

A good deal that goes into a Yocto Project build is simply downloading all of the source

tarballs.

Maybe you have been working with another build system (OpenEmbedded, Angstrom, etc) for which

you've built up a sizable directory of source tarballs.

Or perhaps someone else has such a directory for which you have read access.

If so, you can save time by adding the PREMIRRORS

statement to your configuration file so that local directories are first checked for existing

tarballs before running out to the net:

PREMIRRORS_prepend = "\

git://.*/.* file:///home/you/dl/ \n \

svn://.*/.* file:///home/you/dl/ \n \

cvs://.*/.* file:///home/you/dl/ \n \

ftp://.*/.* file:///home/you/dl/ \n \

http://.*/.* file:///home/you/dl/ \n \

https://.*/.* file:///home/you/dl/ \n"

At this point, you need to select an image to build for the BeagleBoard xM. If this is your first build using the Yocto Project, you should try the smallest and simplest image:

$ bitbake core-image-minimal

Now you just wait for the build to finish.

Here are some variations on the build process that could be helpful:

Fetch all the necessary sources without starting the build:

$ bitbake -c fetchall core-image-minimalThis variation guarantees that you have all the sources for that BitBake target should you disconnect from the net and want to do the build later offline.

Specify to continue the build even if BitBake encounters an error. By default, BitBake aborts the build when it encounters an error. This command keeps a faulty build going:

$ bitbake -k core-image-minimal

Once you have your image, you can take steps to load and boot it on the target hardware.

[1] Kudos and thanks to Robert P. J. Day of CrashCourse for providing the basis for this "expert" section with information from one of his wiki pages.

|

Copyright © 2010-2013 Linux Foundation

Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 UK: England & Wales as published by Creative Commons.

Manual Notes

This version of the Yocto Project Development Manual is for the 1.3.2 release of the Yocto Project. To be sure you have the latest version of the manual for this release, go to the Yocto Project documentation page and select the manual from that site. Manuals from the site are more up-to-date than manuals derived from the Yocto Project released TAR files.

If you located this manual through a web search, the version of the manual might not be the one you want (e.g. the search might have returned a manual much older than the Yocto Project version with which you are working). You can see all Yocto Project major releases by visiting the Releases page. If you need a version of this manual for a different Yocto Project release, visit the Yocto Project documentation page and select the manual set by using the "ACTIVE RELEASES DOCUMENTATION" or "DOCUMENTS ARCHIVE" pull-down menus.

To report any inaccuracies or problems with this manual, send an email to the Yocto Project discussion group at

yocto@yoctoproject.comor log into the freenode#yoctochannel.

| Revision History | |

|---|---|

| Revision 1.1 | 6 October 2011 |

| The initial document released with the Yocto Project 1.1 Release. | |

| Revision 1.2 | April 2012 |

| Released with the Yocto Project 1.2 Release. | |

| Revision 1.3 | October 2012 |

| Released with the Yocto Project 1.3 Release. | |

| Revision 1.3.1 | April 2013 |

| Released with the Yocto Project 1.3.1 Release. | |

| Revision 1.3.2 | May 2013 |

| Released with the Yocto Project 1.3.2 Release. | |

Welcome to the Yocto Project Development Manual! This manual gives you an idea of how to use the Yocto Project to develop embedded Linux images and user-space applications to run on targeted devices. Reading this manual gives you an overview of image, kernel, and user-space application development using the Yocto Project. Because much of the information in this manual is general, it contains many references to other sources where you can find more detail. For example, detailed information on Git, repositories and open source in general can be found in many places. Another example is how to get set up to use the Yocto Project, which our Yocto Project Quick Start covers.

The Yocto Project Development Manual, however, does provide detailed examples on how to change the kernel source code, reconfigure the kernel, and develop an application using the popular Eclipse™ IDE.

The following list describes what you can get from this guide:

Information that lets you get set up to develop using the Yocto Project.

Information to help developers who are new to the open source environment and to the distributed revision control system Git, which the Yocto Project uses.

An understanding of common end-to-end development models and tasks.

Development case overviews for both system development and user-space applications.

An overview and understanding of the emulation environment used with the Yocto Project - the Quick EMUlator (QEMU).

An understanding of basic kernel architecture and concepts.

Many references to other sources of related information.

This manual will not give you the following:

Step-by-step instructions if those instructions exist in other Yocto Project documentation. For example, the Yocto Project Application Developer's Guide contains detailed instruction on how to run the Installing the ADT and Toolchains, which is used to set up a cross-development environment.

Reference material. This type of material resides in an appropriate reference manual. For example, system variables are documented in the Yocto Project Reference Manual.

Detailed public information that is not specific to the Yocto Project. For example, exhaustive information on how to use Git is covered better through the Internet than in this manual.

Because this manual presents overview information for many different topics, you will need to supplement it with other information. The following list presents other sources of information you might find helpful:

The Yocto Project Website: The home page for the Yocto Project provides lots of information on the project as well as links to software and documentation.

Yocto Project Quick Start: This short document lets you get started with the Yocto Project quickly and start building an image.

Yocto Project Reference Manual: This manual is a reference guide to the OpenEmbedded build system known as "Poky." The manual also contains a reference chapter on Board Support Package (BSP) layout.

Yocto Project Application Developer's Guide: This guide provides information that lets you get going with the Application Development Toolkit (ADT) and stand-alone cross-development toolchains to develop projects using the Yocto Project.

Yocto Project Board Support Package (BSP) Developer's Guide: This guide defines the structure for BSP components. Having a commonly understood structure encourages standardization.

Yocto Project Kernel Architecture and Use Manual: This manual describes the architecture of the Yocto Project kernel and provides some work flow examples.

Eclipse IDE Yocto Plug-in: A step-by-step instructional video that demonstrates how an application developer uses Yocto Plug-in features within the Eclipse IDE.

FAQ: A list of commonly asked questions and their answers.

Release Notes: Features, updates and known issues for the current release of the Yocto Project.

Hob: A graphical user interface for BitBake. Hob's primary goal is to enable a user to perform common tasks more easily.

Build Appliance: A bootable custom embedded Linux image you can either build using a non-Linux development system (VMware applications) or download from the Yocto Project website. See the Build Appliance page for more information.

Bugzilla: The bug tracking application the Yocto Project uses. If you find problems with the Yocto Project, you should report them using this application.

Yocto Project Mailing Lists: To subscribe to the Yocto Project mailing lists, click on the following URLs and follow the instructions:

http://lists.yoctoproject.org/listinfo/yocto for a Yocto Project Discussions mailing list.

http://lists.yoctoproject.org/listinfo/poky for a Yocto Project Discussions mailing list about the Poky build system.

http://lists.yoctoproject.org/listinfo/yocto-announce for a mailing list to receive official Yocto Project announcements for developments and as well as Yocto Project milestones.

Internet Relay Chat (IRC): Two IRC channels on freenode are available for Yocto Project and Poky discussions:

#yoctoand#poky, respectively.OpenedHand: The company that initially developed the Poky project, which is the basis for the OpenEmbedded build system used by the Yocto Project. OpenedHand was acquired by Intel Corporation in 2008.

Intel Corporation: A multinational semiconductor chip manufacturer company whose Software and Services Group created and supports the Yocto Project. Intel acquired OpenedHand in 2008.

OpenEmbedded: The build system used by the Yocto Project. This project is the upstream, generic, embedded distribution from which the Yocto Project derives its build system (Poky) from and to which it contributes.

BitBake: The tool used by the OpenEmbedded build system to process project metadata.

BitBake User Manual: A comprehensive guide to the BitBake tool. If you want information on BitBake, see the user manual inculded in the

bitbake/doc/manualdirectory of the Source Directory.Quick EMUlator (QEMU): An open-source machine emulator and virtualizer.

This chapter introduces the Yocto Project and gives you an idea of what you need to get started. You can find enough information to set up your development host and build or use images for hardware supported by the Yocto Project by reading the Yocto Project Quick Start.

The remainder of this chapter summarizes what is in the Yocto Project Quick Start and provides some higher-level concepts you might want to consider.

The Yocto Project is an open-source collaboration project focused on embedded Linux development. The project currently provides a build system, which is referred to as the OpenEmbedded build system in the Yocto Project documentation. The Yocto Project provides various ancillary tools suitable for the embedded developer and also features the Sato reference User Interface, which is optimized for stylus driven, low-resolution screens.

You can use the OpenEmbedded build system, which uses BitBake to develop complete Linux images and associated user-space applications for architectures based on ARM, MIPS, PowerPC, x86 and x86-64. While the Yocto Project does not provide a strict testing framework, it does provide or generate for you artifacts that let you perform target-level and emulated testing and debugging. Additionally, if you are an Eclipse™ IDE user, you can install an Eclipse Yocto Plug-in to allow you to develop within that familiar environment.

Here is what you need to get set up to use the Yocto Project:

Host System: You should have a reasonably current Linux-based host system. You will have the best results with a recent release of Fedora, OpenSUSE, Ubuntu, or CentOS as these releases are frequently tested against the Yocto Project and officially supported. For a list of the distributions under validation and their status, see the "Supported Linux Distributions" section in the Yocto Project Reference Manual and the wiki page at Distribution Support.

You should also have about 100 gigabytes of free disk space for building images.

Packages: The OpenEmbedded build system requires certain packages exist on your development system (e.g. Python 2.6 or 2.7). See "The Packages" section in the Yocto Project Quick Start for the exact package requirements and the installation commands to install them for the supported distributions.

Yocto Project Release: You need a release of the Yocto Project. You set up a with local Source Directory one of two ways depending on whether you are going to contribute back into the Yocto Project or not.

Note

Regardless of the method you use, this manual refers to the resulting local hierarchical set of files as the "Source Directory."Tarball Extraction: If you are not going to contribute back into the Yocto Project, you can simply download a Yocto Project release you want from the website’s download page. Once you have the tarball, just extract it into a directory of your choice.

For example, the following command extracts the Yocto Project 1.3.2 release tarball into the current working directory and sets up the local Source Directory with a top-level folder named

poky-danny-8.0.2:$ tar xfj poky-danny-8.0.2.tar.bz2This method does not produce a local Git repository. Instead, you simply end up with a snapshot of the release.

Git Repository Method: If you are going to be contributing back into the Yocto Project or you simply want to keep up with the latest developments, you should use Git commands to set up a local Git repository of the upstream

pokysource repository. Doing so creates a repository with a complete history of changes and allows you to easily submit your changes upstream to the project. Because you cloned the repository, you have access to all the Yocto Project development branches and tag names used in the upstream repository.The following transcript shows how to clone the

pokyGit repository into the current working directory.Note

You can view the Yocto Project Source Repositories at http://git.yoctoproject.org/cgit.cgiThe command creates the local repository in a directory named

poky. For information on Git used within the Yocto Project, see the "Git" section.$ git clone git://git.yoctoproject.org/poky Initialized empty Git repository in /home/scottrif/poky/.git/ remote: Counting objects: 141863, done. remote: Compressing objects: 100% (38624/38624), done. remote: Total 141863 (delta 99661), reused 141816 (delta 99614) Receiving objects: 100% (141863/141863), 76.64 MiB | 126 KiB/s, done. Resolving deltas: 100% (99661/99661), done.For another example of how to set up your own local Git repositories, see this wiki page, which describes how to create both

pokyandmeta-intelGit repositories.

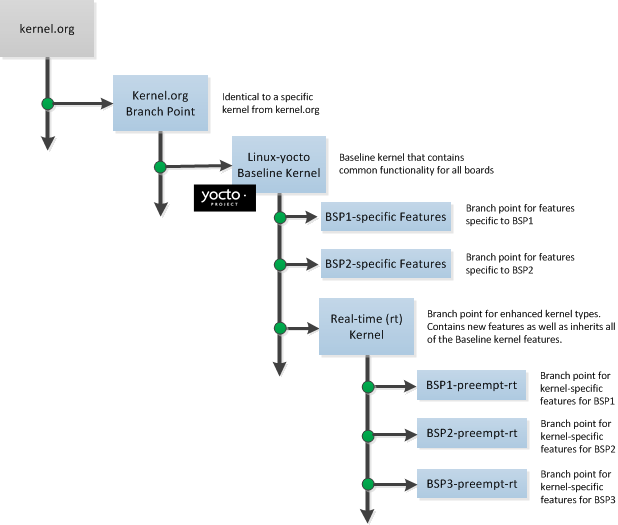

Yocto Project Kernel: If you are going to be making modifications to a supported Yocto Project kernel, you need to establish local copies of the source. You can find Git repositories of supported Yocto Project Kernels organized under "Yocto Linux Kernel" in the Yocto Project Source Repositories at http://git.yoctoproject.org/cgit.cgi.

This setup can involve creating a bare clone of the Yocto Project kernel and then copying that cloned repository. You can create the bare clone and the copy of the bare clone anywhere you like. For simplicity, it is recommended that you create these structures outside of the Source Directory (usually

poky).As an example, the following transcript shows how to create the bare clone of the

linux-yocto-3.4kernel and then create a copy of that clone.Note

When you have a local Yocto Project kernel Git repository, you can reference that repository rather than the upstream Git repository as part of theclonecommand. Doing so can speed up the process.In the following example, the bare clone is named

linux-yocto-3.4.git, while the copy is namedmy-linux-yocto-3.4-work:$ git clone --bare git://git.yoctoproject.org/linux-yocto-3.4 linux-yocto-3.4.git Initialized empty Git repository in /home/scottrif/linux-yocto-3.4.git/ remote: Counting objects: 2468027, done. remote: Compressing objects: 100% (392255/392255), done. remote: Total 2468027 (delta 2071693), reused 2448773 (delta 2052498) Receiving objects: 100% (2468027/2468027), 530.46 MiB | 129 KiB/s, done. Resolving deltas: 100% (2071693/2071693), done.Now create a clone of the bare clone just created:

$ git clone linux-yocto-3.4.git my-linux-yocto-3.4-work Cloning into 'my-linux-yocto-3.4-work'... done.The

poky-extrasGit Repository: Thepoky-extrasGit repository contains metadata needed only if you are modifying and building the kernel image. In particular, it contains the kernel BitBake append (.bbappend) files that you edit to point to your locally modified kernel source files and to build the kernel image. Pointing to these local files is much more efficient than requiring a download of the kernel's source files from upstream each time you make changes to the kernel.You can find the

poky-extrasGit Repository in the "Yocto Metadata Layers" area of the Yocto Project Source Repositories at http://git.yoctoproject.org/cgit.cgi. It is good practice to create this Git repository inside the Source Directory.Following is an example that creates the

poky-extrasGit repository inside the Source Directory, which is namedpokyin this case:$ cd ~/poky $ git clone git://git.yoctoproject.org/poky-extras poky-extras Initialized empty Git repository in /home/scottrif/poky/poky-extras/.git/ remote: Counting objects: 618, done. remote: Compressing objects: 100% (558/558), done. remote: Total 618 (delta 192), reused 307 (delta 39) Receiving objects: 100% (618/618), 526.26 KiB | 111 KiB/s, done. Resolving deltas: 100% (192/192), done.Supported Board Support Packages (BSPs): The Yocto Project provides a layer called

meta-inteland it is maintained in its own separate Git repository. Themeta-intellayer contains many supported BSP Layers.Similar considerations exist for setting up the

meta-intellayer. You can get set up for BSP development one of two ways: tarball extraction or with a local Git repository. It is a good idea to use the same method that you used to set up the Source Directory. Regardless of the method you use, the Yocto Project uses the following BSP layer naming scheme:meta-<BSP_name>where

<BSP_name>is the recognized BSP name. Here are some examples:meta-crownbay meta-emenlow meta-n450See the "BSP Layers" section in the Yocto Project Board Support Package (BSP) Developer's Guide for more information on BSP Layers.

Tarball Extraction: You can download any released BSP tarball from the same download site used to get the Yocto Project release. Once you have the tarball, just extract it into a directory of your choice. Again, this method just produces a snapshot of the BSP layer in the form of a hierarchical directory structure.

Git Repository Method: If you are working with a local Git repository for your Source Directory, you should also use this method to set up the

meta-intelGit repository. You can locate themeta-intelGit repository in the "Yocto Metadata Layers" area of the Yocto Project Source Repositories at http://git.yoctoproject.org/cgit.cgi.Typically, you set up the

meta-intelGit repository inside the Source Directory. For example, the following transcript shows the steps to clone themeta-intelGit repository inside the localpokyGit repository.$ cd ~/poky $ git clone git://git.yoctoproject.org/meta-intel.git Initialized empty Git repository in /home/scottrif/poky/meta-intel/.git/ remote: Counting objects: 3380, done. remote: Compressing objects: 100% (2750/2750), done. remote: Total 3380 (delta 1689), reused 227 (delta 113) Receiving objects: 100% (3380/3380), 1.77 MiB | 128 KiB/s, done. Resolving deltas: 100% (1689/1689), done.The same wiki page referenced earlier covers how to set up the

meta-intelGit repository.

Eclipse Yocto Plug-in: If you are developing applications using the Eclipse Integrated Development Environment (IDE), you will need this plug-in. See the "Setting up the Eclipse IDE" section for more information.

The build process creates an entire Linux distribution, including the toolchain, from source. For more information on this topic, see the "Building an Image" section in the Yocto Project Quick Start.

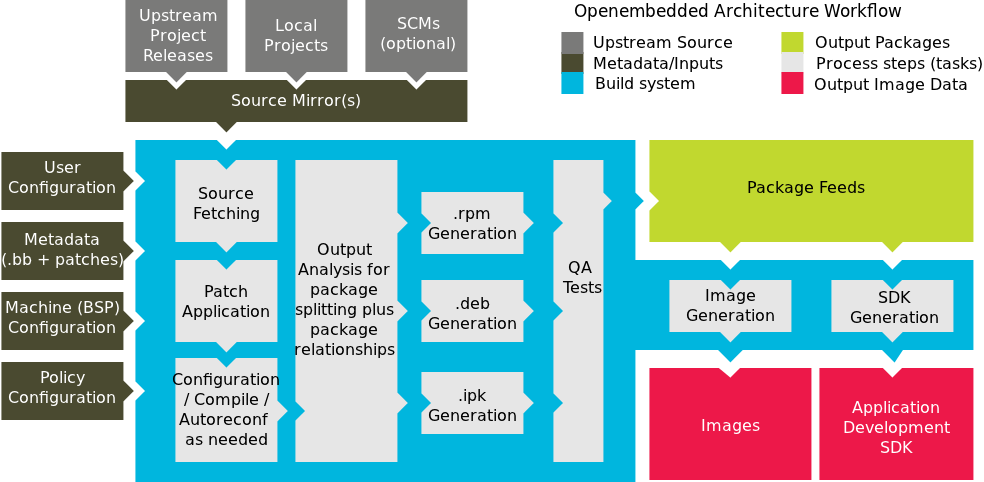

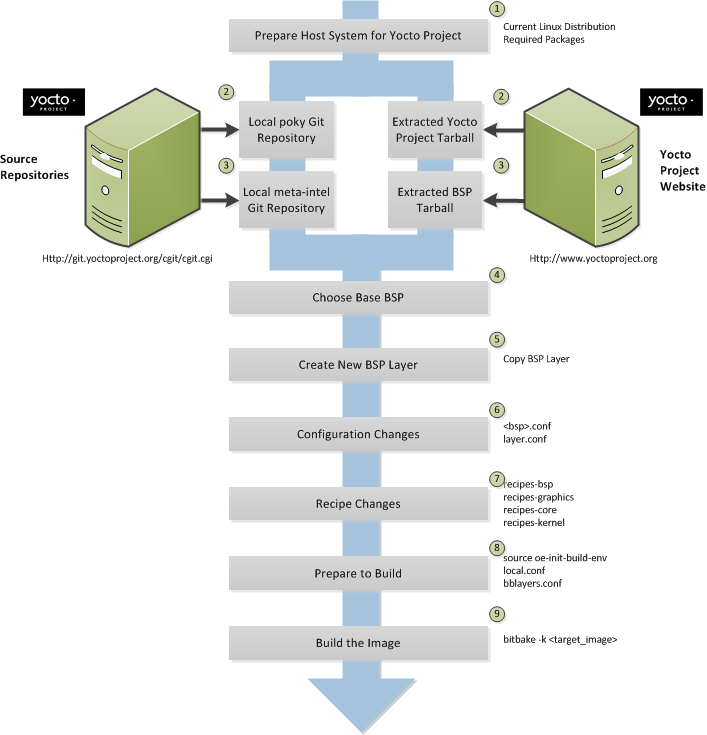

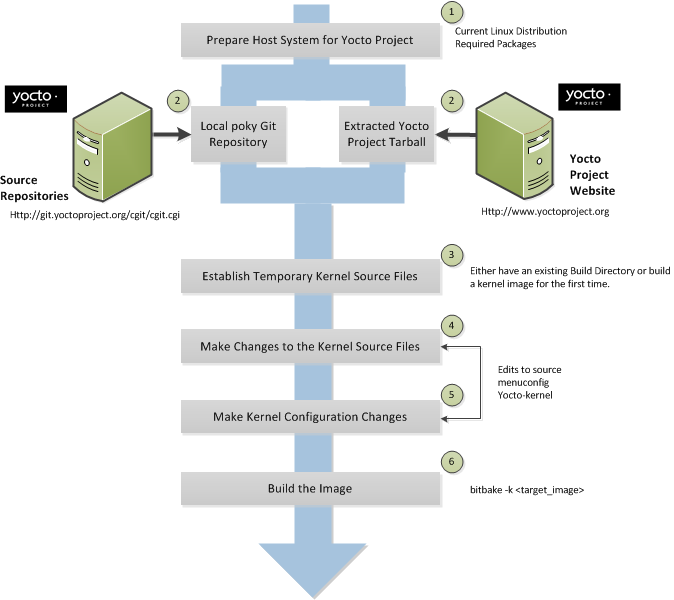

The build process is as follows:

Make sure you have set up the Source Directory described in the previous section.

Initialize the build environment by sourcing a build environment script.

Optionally ensure the

conf/local.confconfiguration file, which is found in the Build Directory, is set up how you want it. This file defines many aspects of the build environment including the target machine architecture through theMACHINEvariable, the development machine's processor use through theBB_NUMBER_THREADSandPARALLEL_MAKEvariables, and a centralized tarball download directory through theDL_DIRvariable.Build the image using the

bitbakecommand. If you want information on BitBake, see the user manual inculded in thebitbake/doc/manualdirectory of the Source Directory.Run the image either on the actual hardware or using the QEMU emulator.

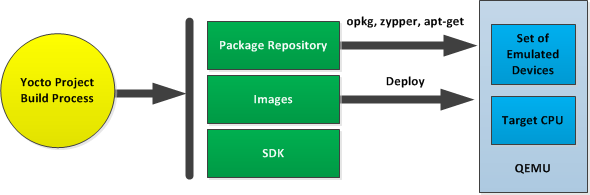

Another option you have to get started is to use pre-built binaries. The Yocto Project provides many types of binaries with each release. See the "Images" chapter in the Yocto Project Reference Manual for descriptions of the types of binaries that ship with a Yocto Project release.

Using a pre-built binary is ideal for developing software applications to run on your target hardware. To do this, you need to be able to access the appropriate cross-toolchain tarball for the architecture on which you are developing. If you are using an SDK type image, the image ships with the complete toolchain native to the architecture. If you are not using an SDK type image, you need to separately download and install the stand-alone Yocto Project cross-toolchain tarball.

Regardless of the type of image you are using, you need to download the pre-built kernel that you will boot in the QEMU emulator and then download and extract the target root filesystem for your target machine’s architecture. You can get architecture-specific binaries and filesystems from machines. You can get installation scripts for stand-alone toolchains from toolchains. Once you have all your files, you set up the environment to emulate the hardware by sourcing an environment setup script. Finally, you start the QEMU emulator. You can find details on all these steps in the "Using Pre-Built Binaries and QEMU" section of the Yocto Project Quick Start.

Using QEMU to emulate your hardware can result in speed issues

depending on the target and host architecture mix.

For example, using the qemux86 image in the emulator

on an Intel-based 32-bit (x86) host machine is fast because the target and

host architectures match.

On the other hand, using the qemuarm image on the same Intel-based

host can be slower.

But, you still achieve faithful emulation of ARM-specific issues.

To speed things up, the QEMU images support using distcc

to call a cross-compiler outside the emulated system.

If you used runqemu to start QEMU, and the

distccd application is present on the host system, any

BitBake cross-compiling toolchain available from the build system is automatically

used from within QEMU simply by calling distcc.

You can accomplish this by defining the cross-compiler variable

(e.g. export CC="distcc").

Alternatively, if you are using a suitable SDK image or the appropriate

stand-alone toolchain is present in /opt/poky,

the toolchain is also automatically used.

Note

Several mechanisms exist that let you connect to the system running on the QEMU emulator:QEMU provides a framebuffer interface that makes standard consoles available.

Generally, headless embedded devices have a serial port. If so, you can configure the operating system of the running image to use that port to run a console. The connection uses standard IP networking.

SSH servers exist in some QEMU images. The

core-image-satoQEMU image has a Dropbear secure shell (ssh) server that runs with the root password disabled. Thecore-image-basicandcore-image-lsbQEMU images have OpenSSH instead of Dropbear. Including these SSH servers allow you to use standardsshandscpcommands. Thecore-image-minimalQEMU image, however, contains no ssh server.You can use a provided, user-space NFS server to boot the QEMU session using a local copy of the root filesystem on the host. In order to make this connection, you must extract a root filesystem tarball by using the

runqemu-extract-sdkcommand. After running the command, you must then point therunqemuscript to the extracted directory instead of a root filesystem image file.

This chapter helps you understand the Yocto Project as an open source development project. In general, working in an open source environment is very different from working in a closed, proprietary environment. Additionally, the Yocto Project uses specific tools and constructs as part of its development environment. This chapter specifically addresses open source philosophy, licensing issues, code repositories, the open source distributed version control system Git, and best practices using the Yocto Project.

Open source philosophy is characterized by software development directed by peer production and collaboration through an active community of developers. Contrast this to the more standard centralized development models used by commercial software companies where a finite set of developers produces a product for sale using a defined set of procedures that ultimately result in an end product whose architecture and source material are closed to the public.

Open source projects conceptually have differing concurrent agendas, approaches, and production. These facets of the development process can come from anyone in the public (community) that has a stake in the software project. The open source environment contains new copyright, licensing, domain, and consumer issues that differ from the more traditional development environment. In an open source environment, the end product, source material, and documentation are all available to the public at no cost.

A benchmark example of an open source project is the Linux Kernel, which was initially conceived and created by Finnish computer science student Linus Torvalds in 1991. Conversely, a good example of a non-open source project is the Windows® family of operating systems developed by Microsoft® Corporation.

Wikipedia has a good historical description of the Open Source Philosophy here. You can also find helpful information on how to participate in the Linux Community here.

It might not be immediately clear how you can use the Yocto Project in a team environment, or scale it for a large team of developers. The specifics of any situation determine the best solution. Granted that the Yocto Project offers immense flexibility regarding this, practices do exist that experience has shown work well.

The core component of any development effort with the Yocto Project is often an automated build and testing framework along with an image generation process. You can use these core components to check that the metadata can be built, highlight when commits break the build, and provide up-to-date images that allow developers to test the end result and use it as a base platform for further development. Experience shows that buildbot is a good fit for this role. What works well is to configure buildbot to make two types of builds: incremental and full (from scratch). See Welcome to the buildbot for the Yocto Project for an example implementation that uses buildbot.

You can tie an incremental build to a commit hook that triggers the build each time a commit is made to the metadata. This practice results in useful acid tests that determine whether a given commit breaks the build in some serious way. Associating a build to a commit can catch a lot of simple errors. Furthermore, the tests are fast so developers can get quick feedback on changes.

Full builds build and test everything from the ground up. These types of builds usually happen at predetermined times like during the night when the machine load is low.

Most teams have many pieces of software undergoing active development at any given time. You can derive large benefits by putting these pieces under the control of a source control system that is compatible (i.e. Git or Subversion (SVN)) with the OpenEmbeded build system that the Yocto Project uses. You can then set the autobuilder to pull the latest revisions of the packages and test the latest commits by the builds. This practice quickly highlights issues. The build system easily supports testing configurations that use both a stable known good revision and a floating revision. The build system can also take just the changes from specific source control branches. This capability allows you to track and test specific changes.

Perhaps the hardest part of setting this up is defining the software project or the metadata policies that surround the different source control systems. Of course circumstances will be different in each case. However, this situation reveals one of the Yocto Project's advantages - the system itself does not force any particular policy on users, unlike a lot of build systems. The system allows the best policies to be chosen for the given circumstances.

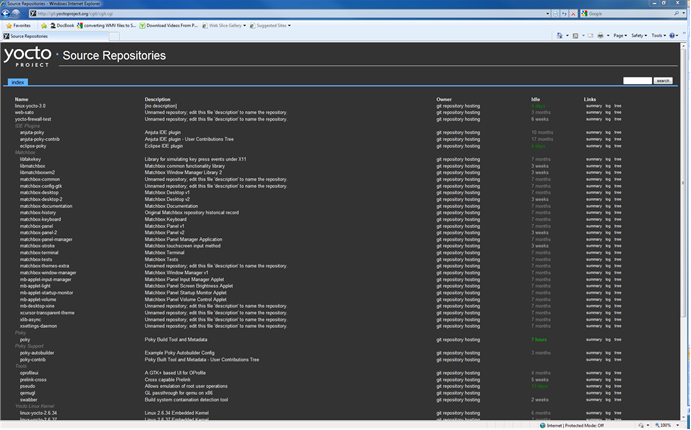

The Yocto Project team maintains complete source repositories for all Yocto Project files at http://git.yoctoproject.org/cgit/cgit.cgi. This web-based source code browser is organized into categories by function such as IDE Plugins, Matchbox, Poky, Yocto Linux Kernel, and so forth. From the interface, you can click on any particular item in the "Name" column and see the URL at the bottom of the page that you need to set up a Git repository for that particular item. Having a local Git repository of the Source Directory (poky) allows you to make changes, contribute to the history, and ultimately enhance the Yocto Project's tools, Board Support Packages, and so forth.

Conversely, if you are a developer that is not interested in contributing back to the Yocto Project, you have the ability to simply download and extract release tarballs and use them within the Yocto Project environment. All that is required is a particular release of the Yocto Project and your application source code.

For any supported release of Yocto Project, you can go to the Yocto Project website’s download page and get a tarball of the release. You can also go to this site to download any supported BSP tarballs. Unpacking the tarball gives you a hierarchical Source Directory that lets you develop using the Yocto Project.

Once you are set up through either tarball extraction or creation of Git repositories, you are ready to develop.

In summary, here is where you can get the project files needed for development:

Source Repositories: This area contains IDE Plugins, Matchbox, Poky, Poky Support, Tools, Yocto Linux Kernel, and Yocto Metadata Layers. You can create local copies of Git repositories for each of these areas.

Index of /releases: This area contains index releases such as the Eclipse™ Yocto Plug-in, miscellaneous support, poky, pseudo, installers for cross-development toolchains, and all released versions of Yocto Project in the form of images or tarballs. Downloading and extracting these files does not produce a local copy of the Git repository but rather a snapshot of a particular release or image.

Yocto Project Download Page This page on the Yocto Project website allows you to download any Yocto Project release or Board Support Package (BSP) in tarball form. The tarballs are similar to those found in the Index of /releases: area.

Following is a list of terms and definitions users new to the Yocto Project development environment might find helpful. While some of these terms are universal, the list includes them just in case:

Append Files: Files that append build information to a recipe file. Append files are known as BitBake append files and

.bbappendfiles. The OpenEmbedded build system expects every append file to have a corresponding and underlying recipe (.bb) file. Furthermore, the append file and the underlying recipe must have the same root filename. The filenames can differ only in the file type suffix used (e.g.formfactor_0.0.bbandformfactor_0.0.bbappend).Information in append files overrides the information in the similarly-named recipe file. For an example of an append file in use, see the "Using .bbappend Files" section.

BitBake: The task executor and scheduler used by the OpenEmbedded build system to build images. For more information on BitBake, see the BitBake documentation in the

bitbake/doc/manualdirectory of the Source Directory.Build Directory: This term refers to the area used by the OpenEmbedded build system for builds. The area is created when you

sourcethe setup environment script that is found in the Source Directory (i.e.oe-init-build-env). TheTOPDIRvariable points to the Build Directory.You have a lot of flexibility when creating the Build Directory. Following are some examples that show how to create the directory:

Create the Build Directory in your current working directory and name it

build. This is the default behavior.$ source poky-danny-8.0.2/oe-init-build-envProvide a directory path and specifically name the build directory. This next example creates a Build Directory named

YP-8.0.2in your home directory within the directorymybuilds. Ifmybuildsdoes not exist, the directory is created for you:$ source poky-danny-8.0.2/oe-init-build-env $HOME/mybuilds/YP-8.0.2Provide an existing directory to use as the Build Directory. This example uses the existing

mybuildsdirectory as the Build Directory.$ source poky-danny-8.0.2/oe-init-build-env $HOME/mybuilds/

Build System: In the context of the Yocto Project this term refers to the OpenEmbedded build system used by the project. This build system is based on the project known as "Poky." For some historical information about Poky, see the Poky term further along in this section.

Classes: Files that provide for logic encapsulation and inheritance allowing commonly used patterns to be defined once and easily used in multiple recipes. Class files end with the

.bbclassfilename extension.Configuration File: Configuration information in various

.conffiles provides global definitions of variables. Theconf/local.confconfiguration file in the Build Directory contains user-defined variables that affect each build. Themeta-yocto/conf/distro/poky.confconfiguration file defines Yocto ‘distro’ configuration variables used only when building with this policy. Machine configuration files, which are located throughout the Source Directory, define variables for specific hardware and are only used when building for that target (e.g. themachine/beagleboard.confconfiguration file defines variables for the Texas Instruments ARM Cortex-A8 development board). Configuration files end with a.conffilename extension.Cross-Development Toolchain: A collection of software development tools and utilities that allow you to develop software for targeted architectures. This toolchain contains cross-compilers, linkers, and debuggers that are specific to an architecture. You can use the OpenEmbedded build system to build a cross-development toolchain installer that when run installs the toolchain that contains the development tools you need to cross-compile and test your software. The Yocto Project ships with images that contain installers for toolchains for supported architectures as well. Sometimes this toolchain is referred to as the meta-toolchain.

Image: An image is the result produced when BitBake processes a given collection of recipes and related metadata. Images are the binary output that run on specific hardware or QEMU and for specific use cases. For a list of the supported image types that the Yocto Project provides, see the "Images" chapter in the Yocto Project Reference Manual.

Layer: A collection of recipes representing the core, a BSP, or an application stack. For a discussion on BSP Layers, see the "BSP Layers" section in the Yocto Project Board Support Packages (BSP) Developer's Guide.

Metadata: The files that BitBake parses when building an image. Metadata includes recipes, classes, and configuration files.

OE-Core: A core set of metadata originating with OpenEmbedded (OE) that is shared between OE and the Yocto Project. This metadata is found in the

metadirectory of the source directory.Package: In the context of the Yocto Project, this term refers to the packaged output from a baked recipe. A package is generally the compiled binaries produced from the recipe's sources. You ‘bake’ something by running it through BitBake.

It is worth noting that the term "package" can, in general, have subtle meanings. For example, the packages refered to in the "The Packages" section are compiled binaries that when installed add functionality to your Linux distribution.

Another point worth noting is that historically within the Yocto Project, recipes were referred to as packages - thus, the existence of several BitBake variables that are seemingly mis-named, (e.g.

PR,PRINC,PV, andPE).Poky: The term "poky" can mean several things. In its most general sense, it is an open-source project that was initially developed by OpenedHand. With OpenedHand, poky was developed off of the existing OpenEmbedded build system becoming a build system for embedded images. After Intel Corporation aquired OpenedHand, the project poky became the basis for the Yocto Project's build system. Within the Yocto Project source repositories, poky exists as a separate Git repository that can be cloned to yield a local copy on the host system. Thus, "poky" can refer to the local copy of the Source Directory used to develop within the Yocto Project.

Recipe: A set of instructions for building packages. A recipe describes where you get source code and which patches to apply. Recipes describe dependencies for libraries or for other recipes, and they also contain configuration and compilation options. Recipes contain the logical unit of execution, the software/images to build, and use the

.bbfile extension.Source Directory: This term refers to the directory structure created as a result of either downloading and unpacking a Yocto Project release tarball or creating a local copy of the

pokyGit repositorygit://git.yoctoproject.org/poky. Sometimes you might here the term "poky directory" used to refer to this directory structure.The Source Directory contains BitBake, Documentation, metadata and other files that all support the Yocto Project. Consequently, you must have the Source Directory in place on your development system in order to do any development using the Yocto Project.

For tarball expansion, the name of the top-level directory of the Source Directory is derived from the Yocto Project release tarball. For example, downloading and unpacking

poky-danny-8.0.2.tar.bz2results in a Source Directory whose top-level folder is namedpoky-danny-8.0.2. If you create a local copy of the Git repository, then you can name the repository anything you like. Throughout much of the documentation,pokyis used as the name of the top-level folder of the local copy of the poky Git repository. So, for example, cloning thepokyGit repository results in a local Git repository whose top-level folder is also namedpoky.It is important to understand the differences between the Source Directory created by unpacking a released tarball as compared to cloning

git://git.yoctoproject.org/poky. When you unpack a tarball, you have an exact copy of the files based on the time of release - a fixed release point. Any changes you make to your local files in the Source Directory are on top of the release. On the other hand, when you clone thepokyGit repository, you have an active development repository. In this case, any local changes you make to the Source Directory can be later applied to active development branches of the upstreampokyGit repository.Finally, if you want to track a set of local changes while starting from the same point as a release tarball, you can create a local Git branch that reflects the exact copy of the files at the time of their release. You do this by using Git tags that are part of the repository.

For more information on concepts around Git repositories, branches, and tags, see the "Repositories, Tags, and Branches" section.

Tasks: Arbitrary groups of software Recipes. You simply use Tasks to hold recipes that, when built, usually accomplish a single task. For example, a task could contain the recipes for a company’s proprietary or value-add software. Or, the task could contain the recipes that enable graphics. A task is really just another recipe. Because task files are recipes, they end with the

.bbfilename extension.Upstream: A reference to source code or repositories that are not local to the development system but located in a master area that is controlled by the maintainer of the source code. For example, in order for a developer to work on a particular piece of code, they need to first get a copy of it from an "upstream" source.

Because open source projects are open to the public, they have different licensing structures in place. License evolution for both Open Source and Free Software has an interesting history. If you are interested in this history, you can find basic information here:

In general, the Yocto Project is broadly licensed under the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) License. MIT licensing permits the reuse of software within proprietary software as long as the license is distributed with that software. MIT is also compatible with the GNU General Public License (GPL). Patches to the Yocto Project follow the upstream licensing scheme. You can find information on the MIT license at here. You can find information on the GNU GPL here.

When you build an image using the Yocto Project, the build process uses a

known list of licenses to ensure compliance.

You can find this list in the Yocto Project files directory at

meta/files/common-licenses.

Once the build completes, the list of all licenses found and used during that build are

kept in the

Build Directory at

tmp/deploy/images/licenses.

If a module requires a license that is not in the base list, the build process generates a warning during the build. These tools make it easier for a developer to be certain of the licenses with which their shipped products must comply. However, even with these tools it is still up to the developer to resolve potential licensing issues.

The base list of licenses used by the build process is a combination of the Software Package Data Exchange (SPDX) list and the Open Source Initiative (OSI) projects. SPDX Group is a working group of the Linux Foundation that maintains a specification for a standard format for communicating the components, licenses, and copyrights associated with a software package. OSI is a corporation dedicated to the Open Source Definition and the effort for reviewing and approving licenses that are OSD-conformant.

You can find a list of the combined SPDX and OSI licenses that the Yocto Project uses here. This wiki page discusses the license infrastructure used by the Yocto Project.

For information that can help you to maintain compliance with various open source licensing during the lifecycle of a product created using the Yocto Project, see the "Maintaining Open Source License Compliance During Your Product's Lifecycle" section.

The Yocto Project uses Git, which is a free, open source distributed version control system. Git supports distributed development, non-linear development, and can handle large projects. It is best that you have some fundamental understanding of how Git tracks projects and how to work with Git if you are going to use Yocto Project for development. This section provides a quick overview of how Git works and provides you with a summary of some essential Git commands.

For more information on Git, see http://git-scm.com/documentation. If you need to download Git, go to http://git-scm.com/download.

As mentioned earlier in section "Yocto Project Source Repositories", the Yocto Project maintains source repositories at http://git.yoctoproject.org/cgit.cgi. If you look at this web-interface of the repositories, each item is a separate Git repository.

Git repositories use branching techniques that track content change (not files) within a project (e.g. a new feature or updated documentation). Creating a tree-like structure based on project divergence allows for excellent historical information over the life of a project. This methodology also allows for an environment in which you can do lots of local experimentation on a project as you develop changes or new features.

A Git repository represents all development efforts for a given project.

For example, the Git repository poky contains all changes

and developments for Poky over the course of its entire life.

That means that all changes that make up all releases are captured.

The repository maintains a complete history of changes.

You can create a local copy of any repository by "cloning" it with the Git

clone command.

When you clone a Git repository, you end up with an identical copy of the

repository on your development system.

Once you have a local copy of a repository, you can take steps to develop locally.

For examples on how to clone Git repositories, see the section

"Getting Set Up" earlier in this manual.

It is important to understand that Git tracks content change and not files.

Git uses "branches" to organize different development efforts.

For example, the poky repository has

bernard,

edison, denzil, danny

and master branches among others.

You can see all the branches by going to

http://git.yoctoproject.org/cgit.cgi/poky/ and

clicking on the

[...]

link beneath the "Branch" heading.

Each of these branches represents a specific area of development.

The master branch represents the current or most recent

development.

All other branches represent off-shoots of the master

branch.

When you create a local copy of a Git repository, the copy has the same set

of branches as the original.

This means you can use Git to create a local working area (also called a branch)

that tracks a specific development branch from the source Git repository.

in other words, you can define your local Git environment to work on any development

branch in the repository.

To help illustrate, here is a set of commands that creates a local copy of the

poky Git repository and then creates and checks out a local

Git branch that tracks the Yocto Project 1.3.2 Release (danny) development:

$ cd ~

$ git clone git://git.yoctoproject.org/poky

$ cd poky

$ git checkout -b danny origin/danny

In this example, the name of the top-level directory of your local Yocto Project

Files Git repository is poky,

and the name of the local working area (or local branch) you have created and checked

out is danny.

The files in your repository now reflect the same files that are in the

danny development branch of the Yocto Project's

poky repository.

It is important to understand that when you create and checkout a

local working branch based on a branch name,

your local environment matches the "tip" of that development branch

at the time you created your local branch, which could be

different than the files at the time of a similarly named release.

In other words, creating and checking out a local branch based on the

danny branch name is not the same as

cloning and checking out the master branch.

Keep reading to see how you create a local snapshot of a Yocto Project Release.

Git uses "tags" to mark specific changes in a repository.

Typically, a tag is used to mark a special point such as the final change

before a project is released.

You can see the tags used with the poky Git repository

by going to http://git.yoctoproject.org/cgit.cgi/poky/ and

clicking on the

[...]

link beneath the "Tag" heading.

Some key tags are bernard-5.0, denzil-7.0,

and danny-8.0.2.

These tags represent Yocto Project releases.

When you create a local copy of the Git repository, you also have access to all the tags. Similar to branches, you can create and checkout a local working Git branch based on a tag name. When you do this, you get a snapshot of the Git repository that reflects the state of the files when the change was made associated with that tag. The most common use is to checkout a working branch that matches a specific Yocto Project release. Here is an example:

$ cd ~

$ git clone git://git.yoctoproject.org/poky

$ cd poky

$ git checkout -b my-danny-8.0.2 danny-8.0.2

In this example, the name of the top-level directory of your local Yocto Project

Files Git repository is poky.

And, the name of the local branch you have created and checked out is

my-danny-8.0.2.

The files in your repository now exactly match the Yocto Project 1.3.2

Release tag (danny-8.0.2).

It is important to understand that when you create and checkout a local

working branch based on a tag, your environment matches a specific point

in time and not a development branch.

Git has an extensive set of commands that lets you manage changes and perform collaboration over the life of a project. Conveniently though, you can manage with a small set of basic operations and workflows once you understand the basic philosophy behind Git. You do not have to be an expert in Git to be functional. A good place to look for instruction on a minimal set of Git commands is here. If you need to download Git, you can do so here.

If you don’t know much about Git, we suggest you educate yourself by visiting the links previously mentioned.

The following list briefly describes some basic Git operations as a way to get started. As with any set of commands, this list (in most cases) simply shows the base command and omits the many arguments they support. See the Git documentation for complete descriptions and strategies on how to use these commands:

git init: Initializes an empty Git repository. You cannot use Git commands unless you have a.gitrepository.git clone: Creates a clone of a repository. During collaboration, this command allows you to create a local repository that is on equal footing with a fellow developer’s repository.git add: Adds updated file contents to the index that Git uses to track changes. You must add all files that have changed before you can commit them.git commit: Creates a “commit” that documents the changes you made. Commits are used for historical purposes, for determining if a maintainer of a project will allow the change, and for ultimately pushing the change from your local Git repository into the project’s upstream (or master) repository.git status: Reports any modified files that possibly need to be added and committed.git checkout <branch-name>: Changes your working branch. This command is analogous to “cd”.git checkout –b <working-branch>: Creates a working branch on your local machine where you can isolate work. It is a good idea to use local branches when adding specific features or changes. This way if you don’t like what you have done you can easily get rid of the work.git branch: Reports existing local branches and tells you the branch in which you are currently working.git branch -D <branch-name>: Deletes an existing local branch. You need to be in a local branch other than the one you are deleting in order to delete<branch-name>.git pull: Retrieves information from an upstream Git repository and places it in your local Git repository. You use this command to make sure you are synchronized with the repository from which you are basing changes (.e.g. the master branch).git push: Sends all your local changes you have committed to an upstream Git repository (e.g. a contribution repository). The maintainer of the project draws from these repositories when adding your changes to the project’s master repository.git merge: Combines or adds changes from one local branch of your repository with another branch. When you create a local Git repository, the default branch is named “master”. A typical workflow is to create a temporary branch for isolated work, make and commit your changes, switch to your local master branch, merge the changes from the temporary branch into the local master branch, and then delete the temporary branch.git cherry-pick: Choose and apply specific commits from one branch into another branch. There are times when you might not be able to merge all the changes in one branch with another but need to pick out certain ones.gitk: Provides a GUI view of the branches and changes in your local Git repository. This command is a good way to graphically see where things have diverged in your local repository.git log: Reports a history of your changes to the repository.git diff: Displays line-by-line differences between your local working files and the same files in the upstream Git repository that your branch currently tracks.

This section provides some overview on workflows using Git. In particular, the information covers basic practices that describe roles and actions in a collaborative development environment. Again, if you are familiar with this type of development environment, you might want to just skip this section.

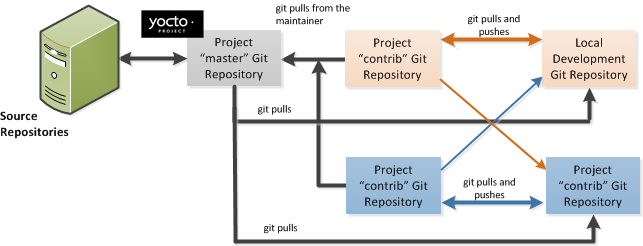

The Yocto Project files are maintained using Git in a "master" branch whose Git history tracks every change and whose structure provides branches for all diverging functionality. Although there is no need to use Git, many open source projects do so. For the Yocto Project, a key individual called the "maintainer" is responsible for the "master" branch of the Git repository. The "master" branch is the “upstream” repository where the final builds of the project occur. The maintainer is responsible for allowing changes in from other developers and for organizing the underlying branch structure to reflect release strategies and so forth.

Note

You can see who is the maintainer for Yocto Project files by examining thedistro_tracking_fields.inc file in the Yocto Project

meta/conf/distro/include directory.

The project also has contribution repositories known as “contrib” areas. These areas temporarily hold changes to the project that have been submitted or committed by the Yocto Project development team and by community members that contribute to the project. The maintainer determines if the changes are qualified to be moved from the "contrib" areas into the "master" branch of the Git repository.

Developers (including contributing community members) create and maintain cloned repositories of the upstream "master" branch. These repositories are local to their development platforms and are used to develop changes. When a developer is satisfied with a particular feature or change, they “push” the changes to the appropriate "contrib" repository.

Developers are responsible for keeping their local repository up-to-date with "master". They are also responsible for straightening out any conflicts that might arise within files that are being worked on simultaneously by more than one person. All this work is done locally on the developer’s machine before anything is pushed to a "contrib" area and examined at the maintainer’s level.