3 Basic Usage (with examples) for each of the Yocto Tracing Tools

This chapter presents basic usage examples for each of the tracing tools.

3.1 perf

The perf tool is the profiling and tracing tool that comes bundled with the Linux kernel.

Don’t let the fact that it’s part of the kernel fool you into thinking that it’s only for tracing and profiling the kernel — you can indeed use it to trace and profile just the kernel, but you can also use it to profile specific applications separately (with or without kernel context), and you can also use it to trace and profile the kernel and all applications on the system simultaneously to gain a system-wide view of what’s going on.

In many ways, perf aims to be a superset of all the tracing and profiling tools available in Linux today, including all the other tools covered in this How-to. The past couple of years have seen perf subsume a lot of the functionality of those other tools and, at the same time, those other tools have removed large portions of their previous functionality and replaced it with calls to the equivalent functionality now implemented by the perf subsystem. Extrapolation suggests that at some point those other tools will become completely redundant and go away; until then, we’ll cover those other tools in these pages and in many cases show how the same things can be accomplished in perf and the other tools when it seems useful to do so.

The coverage below details some of the most common ways you’ll likely want to apply the tool; full documentation can be found either within the tool itself or in the manual pages at perf(1).

3.1.1 perf Setup

For this section, we’ll assume you’ve already performed the basic setup outlined in the “General Setup” section.

In particular, you’ll get the most mileage out of perf if you profile an

image built with the following in your local.conf file:

INHIBIT_PACKAGE_STRIP = "1"

perf runs on the target system for the most part. You can archive profile data and copy it to the host for analysis, but for the rest of this document we assume you’re connected to the host through SSH and will be running the perf commands on the target.

3.1.2 Basic perf Usage

The perf tool is pretty much self-documenting. To remind yourself of the

available commands, just type perf, which will show you basic usage

along with the available perf subcommands:

root@crownbay:~# perf

usage: perf [--version] [--help] COMMAND [ARGS]

The most commonly used perf commands are:

annotate Read perf.data (created by perf record) and display annotated code

archive Create archive with object files with build-ids found in perf.data file

bench General framework for benchmark suites

buildid-cache Manage build-id cache.

buildid-list List the buildids in a perf.data file

diff Read two perf.data files and display the differential profile

evlist List the event names in a perf.data file

inject Filter to augment the events stream with additional information

kmem Tool to trace/measure kernel memory(slab) properties

kvm Tool to trace/measure kvm guest os

list List all symbolic event types

lock Analyze lock events

probe Define new dynamic tracepoints

record Run a command and record its profile into perf.data

report Read perf.data (created by perf record) and display the profile

sched Tool to trace/measure scheduler properties (latencies)

script Read perf.data (created by perf record) and display trace output

stat Run a command and gather performance counter statistics

test Runs sanity tests.

timechart Tool to visualize total system behavior during a workload

top System profiling tool.

See 'perf help COMMAND' for more information on a specific command.

3.1.2.1 Using perf to do Basic Profiling

As a simple test case, we’ll profile the wget of a fairly large file,

which is a minimally interesting case because it has both file and

network I/O aspects, and at least in the case of standard Yocto images,

it’s implemented as part of BusyBox, so the methods we use to analyze it

can be used in a similar way to the whole host of supported BusyBox

applets in Yocto:

root@crownbay:~# rm linux-2.6.19.2.tar.bz2; \

wget https://downloads.yoctoproject.org/mirror/sources/linux-2.6.19.2.tar.bz2

The quickest and easiest way to get some basic overall data about what’s

going on for a particular workload is to profile it using perf stat.

This command basically profiles using a few default counters and displays

the summed counts at the end of the run:

root@crownbay:~# perf stat wget https://downloads.yoctoproject.org/mirror/sources/linux-2.6.19.2.tar.bz2

Connecting to downloads.yoctoproject.org (140.211.169.59:80)

linux-2.6.19.2.tar.b 100% |***************************************************| 41727k 0:00:00 ETA

Performance counter stats for 'wget https://downloads.yoctoproject.org/mirror/sources/linux-2.6.19.2.tar.bz2':

4597.223902 task-clock # 0.077 CPUs utilized

23568 context-switches # 0.005 M/sec

68 CPU-migrations # 0.015 K/sec

241 page-faults # 0.052 K/sec

3045817293 cycles # 0.663 GHz

<not supported> stalled-cycles-frontend

<not supported> stalled-cycles-backend

858909167 instructions # 0.28 insns per cycle

165441165 branches # 35.987 M/sec

19550329 branch-misses # 11.82% of all branches

59.836627620 seconds time elapsed

Such a simple-minded test doesn’t always yield much of interest, but sometimes it does (see the Slow write speed on live images with denzil bug report).

Also, note that perf stat isn’t restricted to a fixed set of counters

— basically any event listed in the output of perf list can be tallied

by perf stat. For example, suppose we wanted to see a summary of all

the events related to kernel memory allocation/freeing along with cache

hits and misses:

root@crownbay:~# perf stat -e kmem:* -e cache-references -e cache-misses wget https://downloads.yoctoproject.org/mirror/sources/linux-2.6.19.2.tar.bz2

Connecting to downloads.yoctoproject.org (140.211.169.59:80)

linux-2.6.19.2.tar.b 100% |***************************************************| 41727k 0:00:00 ETA

Performance counter stats for 'wget https://downloads.yoctoproject.org/mirror/sources/linux-2.6.19.2.tar.bz2':

5566 kmem:kmalloc

125517 kmem:kmem_cache_alloc

0 kmem:kmalloc_node

0 kmem:kmem_cache_alloc_node

34401 kmem:kfree

69920 kmem:kmem_cache_free

133 kmem:mm_page_free

41 kmem:mm_page_free_batched

11502 kmem:mm_page_alloc

11375 kmem:mm_page_alloc_zone_locked

0 kmem:mm_page_pcpu_drain

0 kmem:mm_page_alloc_extfrag

66848602 cache-references

2917740 cache-misses # 4.365 % of all cache refs

44.831023415 seconds time elapsed

As you can see, perf stat gives us a nice easy

way to get a quick overview of what might be happening for a set of

events, but normally we’d need a little more detail in order to

understand what’s going on in a way that we can act on in a useful way.

To dive down into a next level of detail, we can use perf record /

perf report which will collect profiling data and present it to use using an

interactive text-based UI (or just as text if we specify --stdio to

perf report).

As our first attempt at profiling this workload, we’ll just run perf

record, handing it the workload we want to profile (everything after

perf record and any perf options we hand it — here none, will be

executed in a new shell). perf collects samples until the process exits

and records them in a file named perf.data in the current working

directory:

root@crownbay:~# perf record wget https://downloads.yoctoproject.org/mirror/sources/linux-2.6.19.2.tar.bz2

Connecting to downloads.yoctoproject.org (140.211.169.59:80)

linux-2.6.19.2.tar.b 100% |************************************************| 41727k 0:00:00 ETA

[ perf record: Woken up 1 times to write data ]

[ perf record: Captured and wrote 0.176 MB perf.data (~7700 samples) ]

To see the results in a

“text-based UI” (tui), just run perf report, which will read the

perf.data file in the current working directory and display the results

in an interactive UI:

root@crownbay:~# perf report

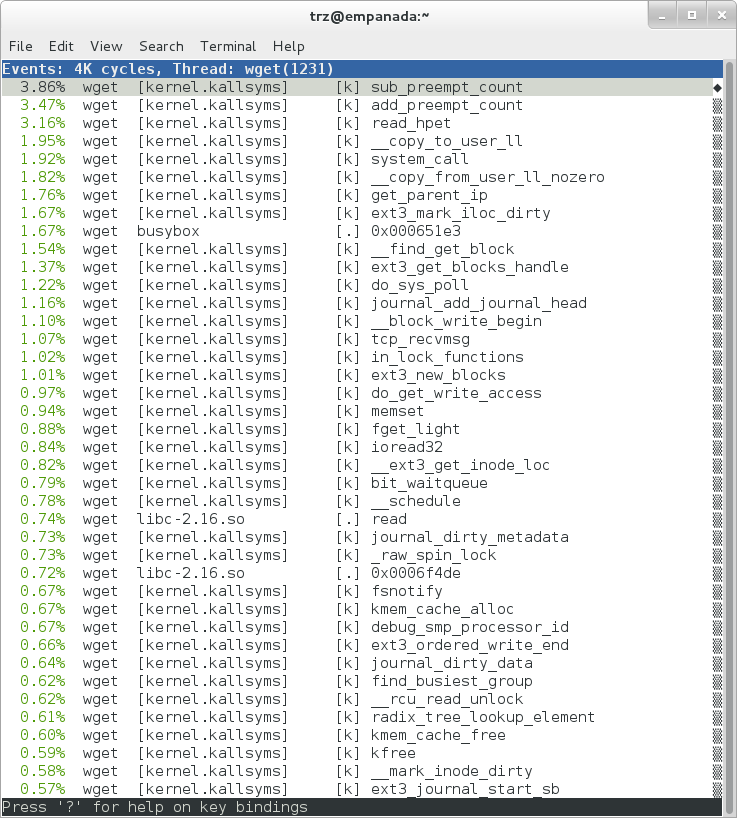

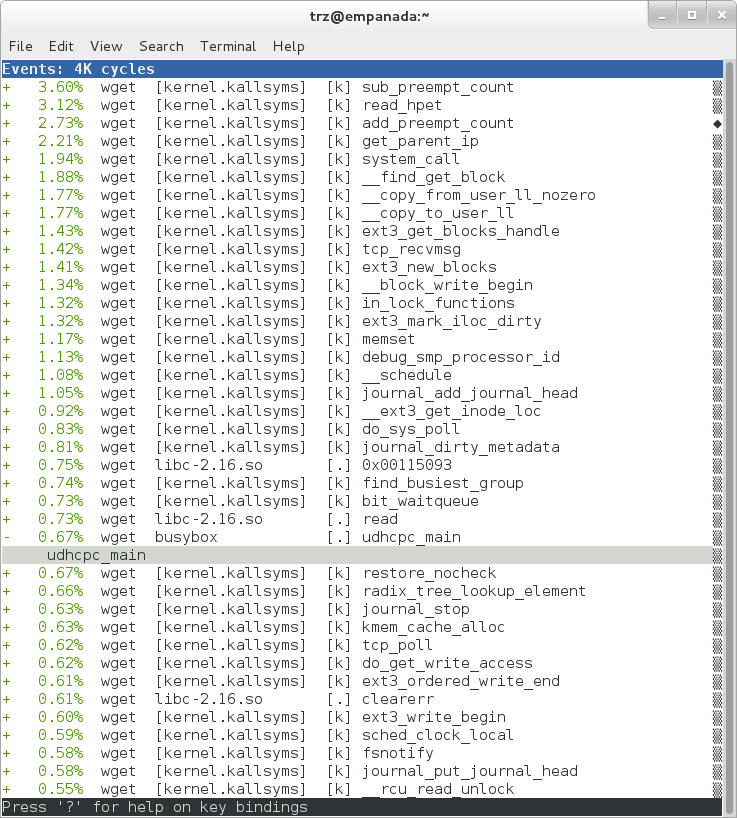

The above screenshot displays a “flat” profile, one entry for each

“bucket” corresponding to the functions that were profiled during the

profiling run, ordered from the most popular to the least (perf has

options to sort in various orders and keys as well as display entries

only above a certain threshold and so on — see the perf documentation

for details). Note that this includes both user space functions (entries

containing a [.]) and kernel functions accounted to the process (entries

containing a [k]). perf has command-line modifiers that can be used to

restrict the profiling to kernel or user space, among others.

Notice also that the above report shows an entry for busybox, which is

the executable that implements wget in Yocto, but that instead of a

useful function name in that entry, it displays a not-so-friendly hex

value instead. The steps below will show how to fix that problem.

Before we do that, however, let’s try running a different profile, one

which shows something a little more interesting. The only difference

between the new profile and the previous one is that we’ll add the -g

option, which will record not just the address of a sampled function,

but the entire call chain to the sampled function as well:

root@crownbay:~# perf record -g wget https://downloads.yoctoproject.org/mirror/sources/linux-2.6.19.2.tar.bz2

Connecting to downloads.yoctoproject.org (140.211.169.59:80)

linux-2.6.19.2.tar.b 100% |************************************************| 41727k 0:00:00 ETA

[ perf record: Woken up 3 times to write data ]

[ perf record: Captured and wrote 0.652 MB perf.data (~28476 samples) ]

root@crownbay:~# perf report

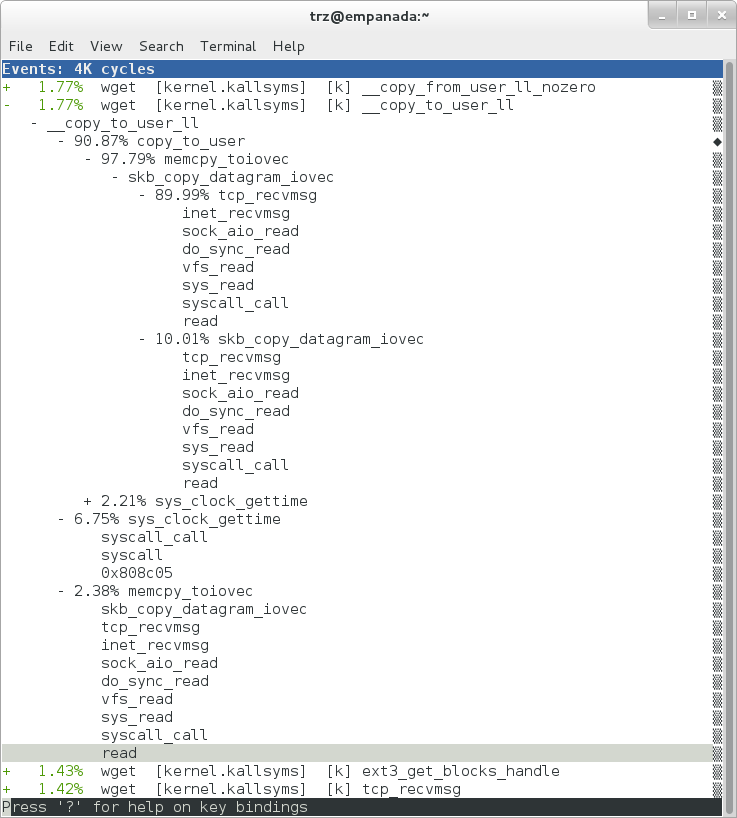

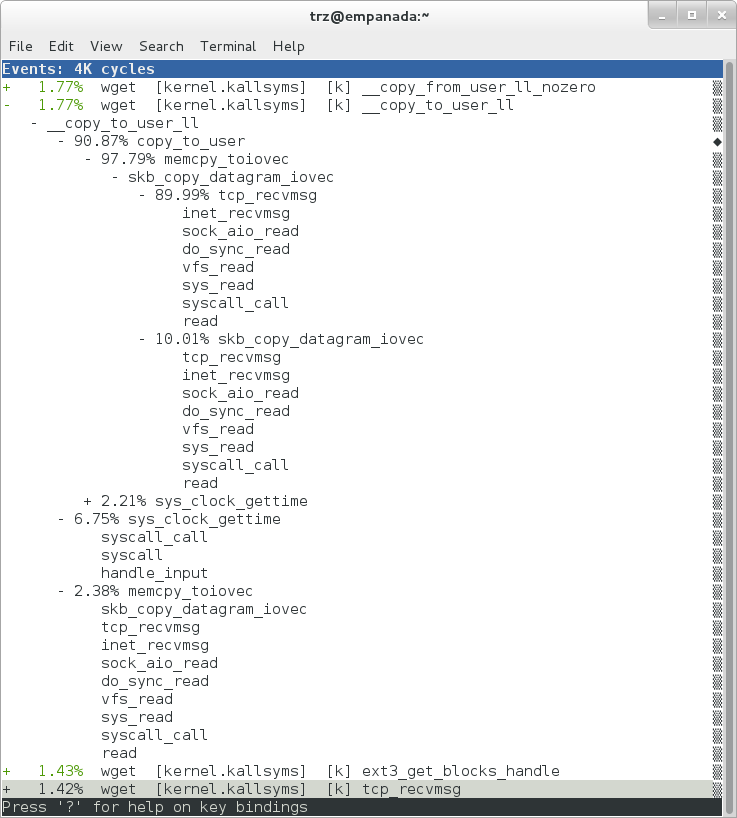

Using the call graph view, we can actually see not only which functions took the most time, but we can also see a summary of how those functions were called and learn something about how the program interacts with the kernel in the process.

Notice that each entry in the above screenshot now contains a + on the

left side. This means that we can expand the entry and drill down

into the call chains that feed into that entry. Pressing Enter on any

one of them will expand the call chain (you can also press E to expand

them all at the same time or C to collapse them all).

In the screenshot above, we’ve toggled the __copy_to_user_ll() entry

and several subnodes all the way down. This lets us see which call chains

contributed to the profiled __copy_to_user_ll() function which

contributed 1.77% to the total profile.

As a bit of background explanation for these call chains, think about

what happens at a high level when you run wget to get a file out on the

network. Basically what happens is that the data comes into the kernel

via the network connection (socket) and is passed to the user space

program wget (which is actually a part of BusyBox, but that’s not

important for now), which takes the buffers the kernel passes to it and

writes it to a disk file to save it.

The part of this process that we’re looking at in the above call stacks

is the part where the kernel passes the data it has read from the socket

down to wget i.e. a copy-to-user.

Notice also that here there’s also a case where the hex value is

displayed in the call stack, here in the expanded sys_clock_gettime()

function. Later we’ll see it resolve to a user space function call in

BusyBox.

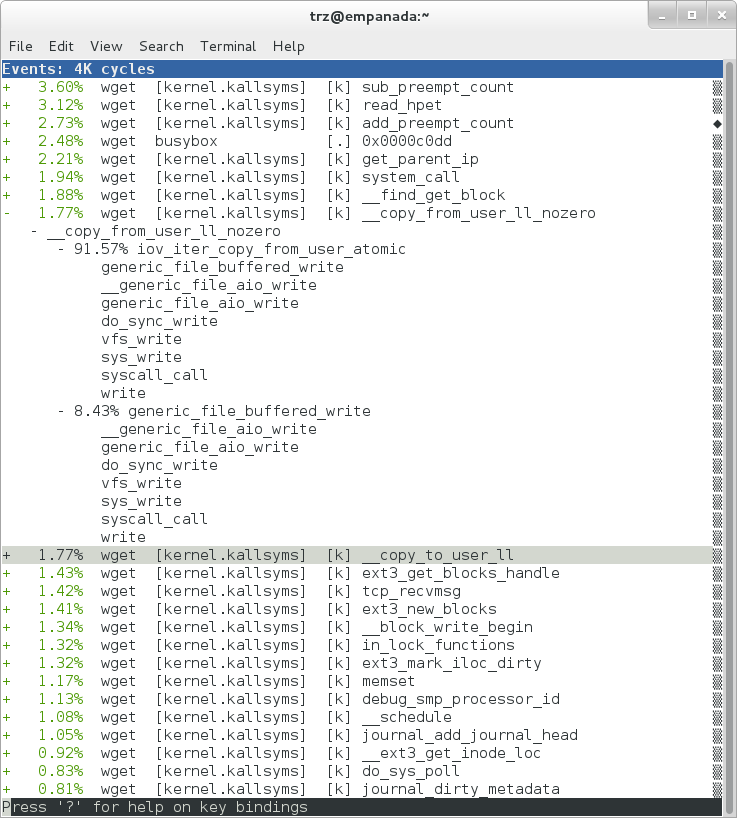

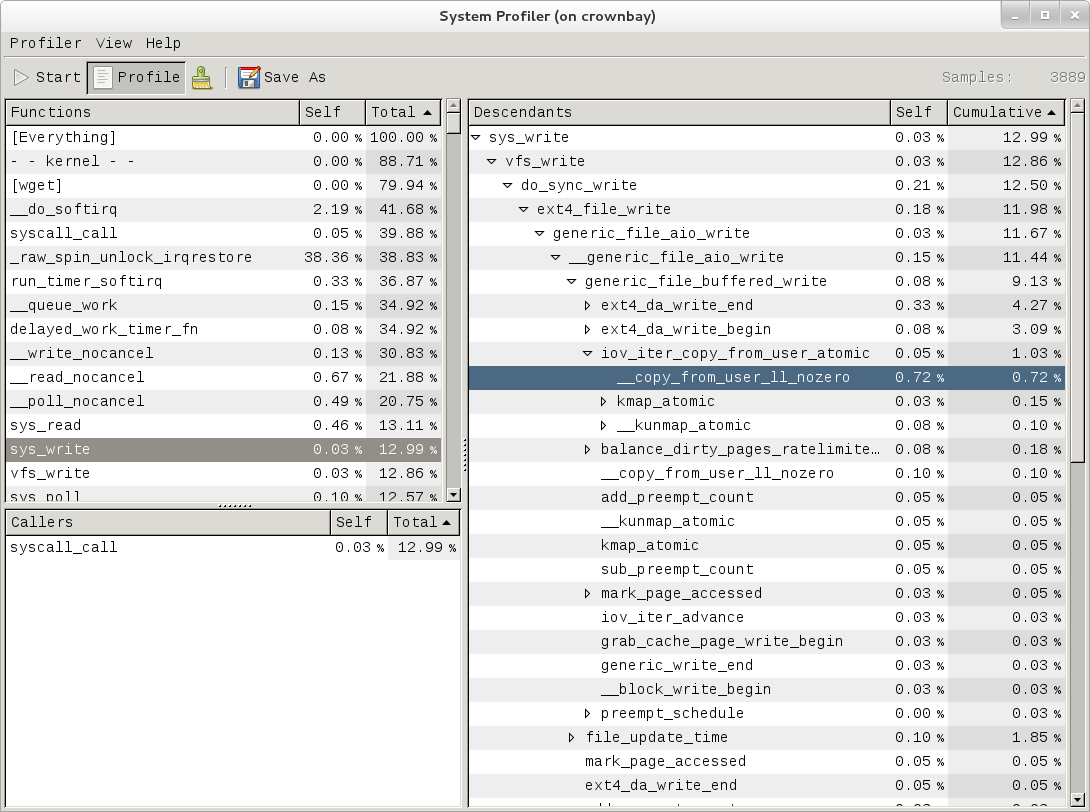

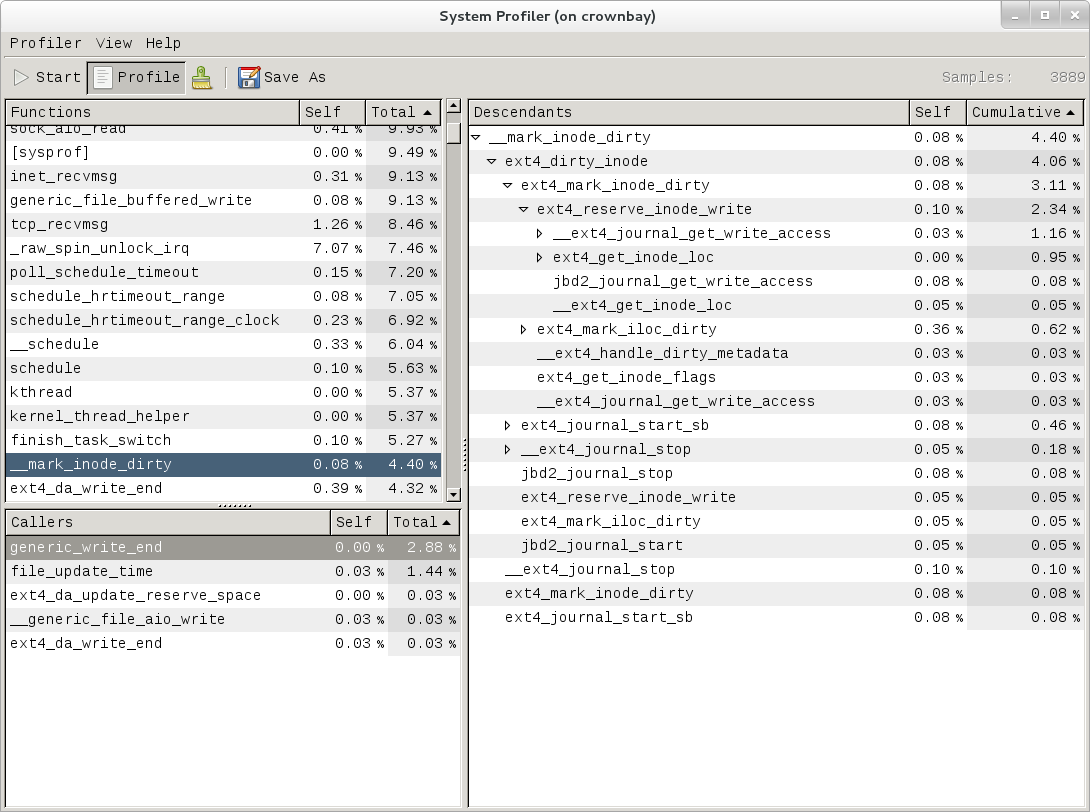

The above screenshot shows the other half of the journey for the data —

from the wget program’s user space buffers to disk. To get the buffers to

disk, the wget program issues a write(2), which does a copy-from-user to

the kernel, which then takes care via some circuitous path (probably

also present somewhere in the profile data), to get it safely to disk.

Now that we’ve seen the basic layout of the profile data and the basics

of how to extract useful information out of it, let’s get back to the

task at hand and see if we can get some basic idea about where the time

is spent in the program we’re profiling, wget. Remember that wget is

actually implemented as an applet in BusyBox, so while the process name

is wget, the executable we’re actually interested in is busybox.

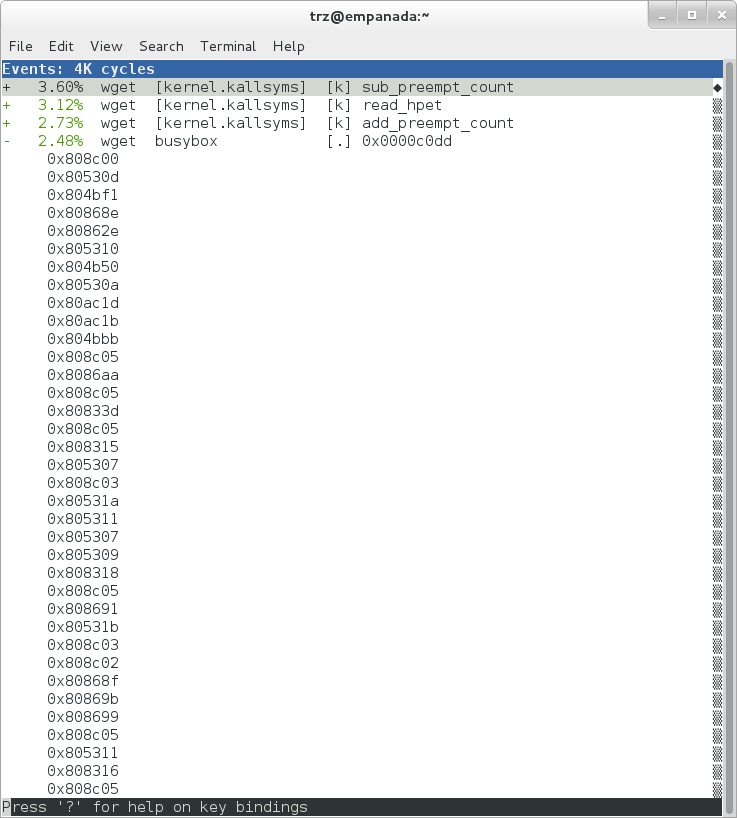

Therefore, let’s expand the first entry containing BusyBox:

Again, before we expanded we saw that the function was labeled with a hex value instead of a symbol as with most of the kernel entries. Expanding the BusyBox entry doesn’t make it any better.

The problem is that perf can’t find the symbol information for the

busybox binary, which is actually stripped out by the Yocto build

system.

One way around that is to put the following in your local.conf file

when you build the image:

INHIBIT_PACKAGE_STRIP = "1"

However, we already have an image with the binaries stripped, so what can we do to get perf to resolve the symbols? Basically we need to install the debugging information for the BusyBox package.

To generate the debug info for the packages in the image, we can add

dbg-pkgs to EXTRA_IMAGE_FEATURES in local.conf. For example:

EXTRA_IMAGE_FEATURES = "debug-tweaks tools-profile dbg-pkgs"

Additionally, in order to generate the type of debugging information that perf

understands, we also need to set PACKAGE_DEBUG_SPLIT_STYLE

in the local.conf file:

PACKAGE_DEBUG_SPLIT_STYLE = 'debug-file-directory'

Once we’ve done that, we can install the debugging information for BusyBox. The

debug packages once built can be found in build/tmp/deploy/rpm/*

on the host system. Find the busybox-dbg-...rpm file and copy it

to the target. For example:

[trz@empanada core2]$ scp /home/trz/yocto/crownbay-tracing-dbg/build/tmp/deploy/rpm/core2_32/busybox-dbg-1.20.2-r2.core2_32.rpm root@192.168.1.31:

busybox-dbg-1.20.2-r2.core2_32.rpm 100% 1826KB 1.8MB/s 00:01

Now install the debug RPM on the target:

root@crownbay:~# rpm -i busybox-dbg-1.20.2-r2.core2_32.rpm

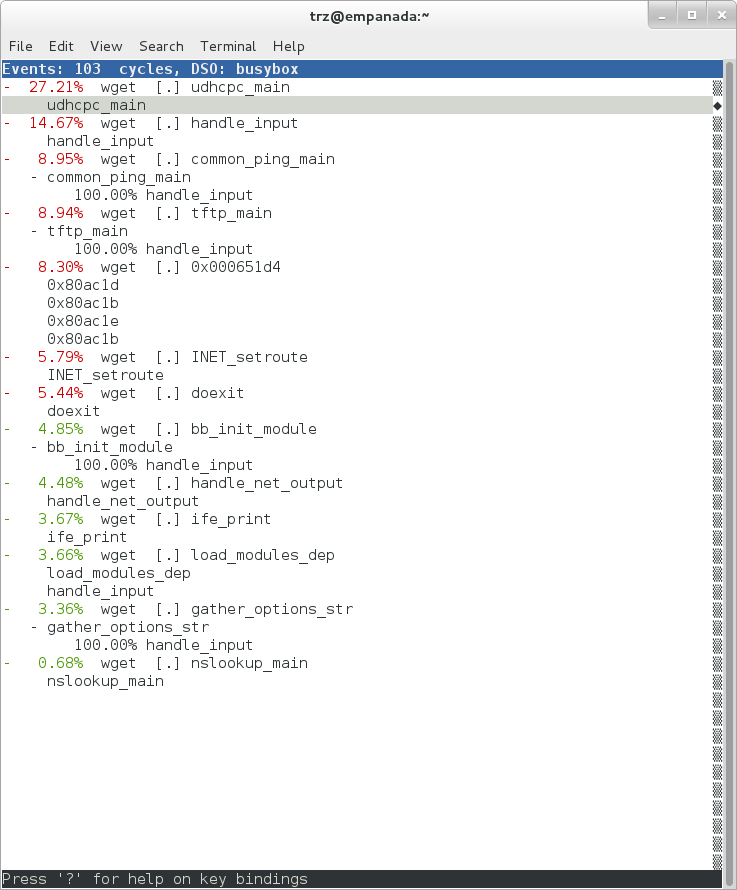

Now that the debugging information is installed, we see that the BusyBox entries now display their functions symbolically:

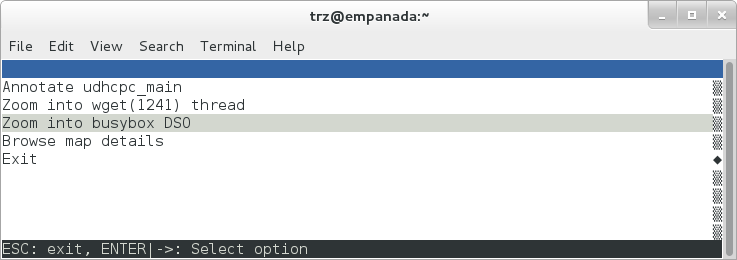

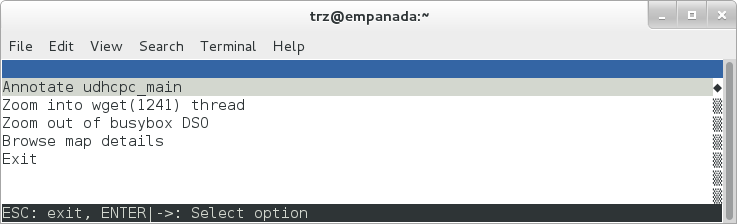

If we expand one of the entries and press Enter on a leaf node, we’re

presented with a menu of actions we can take to get more information

related to that entry:

One of these actions allows us to show a view that displays a

busybox-centric view of the profiled functions (in this case we’ve also

expanded all the nodes using the E key):

Finally, we can see that now that the BusyBox debugging information is installed,

the previously unresolved symbol in the sys_clock_gettime() entry

mentioned previously is now resolved, and shows that the

sys_clock_gettime system call that was the source of 6.75% of the

copy-to-user overhead was initiated by the handle_input() BusyBox

function:

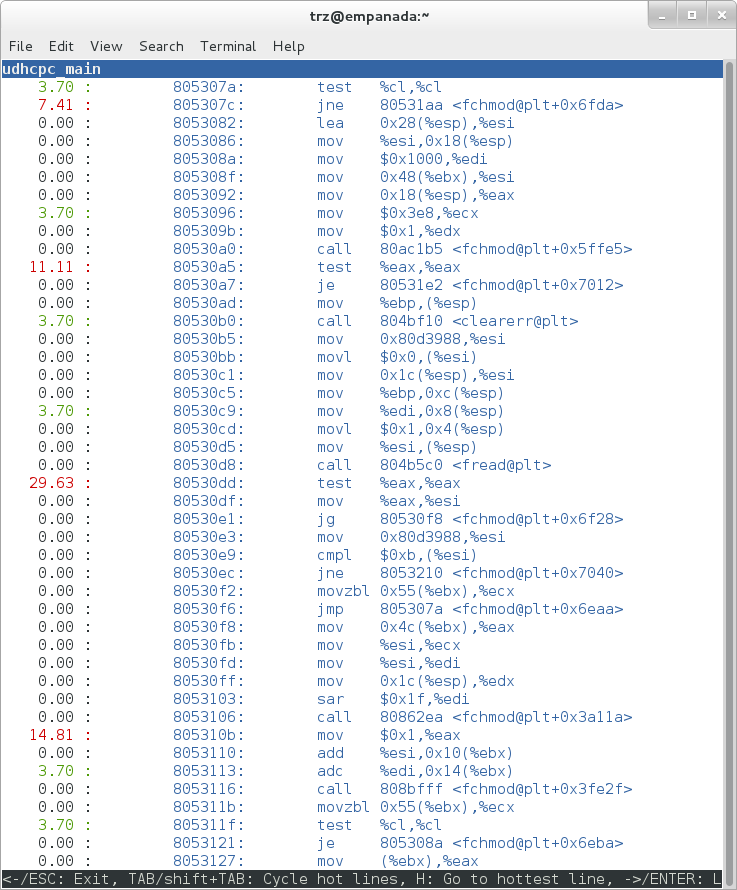

At the lowest level of detail, we can dive down to the assembly level

and see which instructions caused the most overhead in a function.

Pressing Enter on the udhcpc_main function, we’re again presented

with a menu:

Selecting Annotate udhcpc_main, we get a detailed listing of

percentages by instruction for the udhcpc_main function. From the

display, we can see that over 50% of the time spent in this function is

taken up by a couple tests and the move of a constant (1) to a register:

As a segue into tracing, let’s try another profile using a different

counter, something other than the default cycles.

The tracing and profiling infrastructure in Linux has become unified in a way that allows us to use the same tool with a completely different set of counters, not just the standard hardware counters that traditional tools have had to restrict themselves to (the traditional tools can now actually make use of the expanded possibilities now available to them, and in some cases have, as mentioned previously).

We can get a list of the available events that can be used to profile a

workload via perf list:

root@crownbay:~# perf list

List of pre-defined events (to be used in -e):

cpu-cycles OR cycles [Hardware event]

stalled-cycles-frontend OR idle-cycles-frontend [Hardware event]

stalled-cycles-backend OR idle-cycles-backend [Hardware event]

instructions [Hardware event]

cache-references [Hardware event]

cache-misses [Hardware event]

branch-instructions OR branches [Hardware event]

branch-misses [Hardware event]

bus-cycles [Hardware event]

ref-cycles [Hardware event]

cpu-clock [Software event]

task-clock [Software event]

page-faults OR faults [Software event]

minor-faults [Software event]

major-faults [Software event]

context-switches OR cs [Software event]

cpu-migrations OR migrations [Software event]

alignment-faults [Software event]

emulation-faults [Software event]

L1-dcache-loads [Hardware cache event]

L1-dcache-load-misses [Hardware cache event]

L1-dcache-prefetch-misses [Hardware cache event]

L1-icache-loads [Hardware cache event]

L1-icache-load-misses [Hardware cache event]

.

.

.

rNNN [Raw hardware event descriptor]

cpu/t1=v1[,t2=v2,t3 ...]/modifier [Raw hardware event descriptor]

(see 'perf list --help' on how to encode it)

mem:<addr>[:access] [Hardware breakpoint]

sunrpc:rpc_call_status [Tracepoint event]

sunrpc:rpc_bind_status [Tracepoint event]

sunrpc:rpc_connect_status [Tracepoint event]

sunrpc:rpc_task_begin [Tracepoint event]

skb:kfree_skb [Tracepoint event]

skb:consume_skb [Tracepoint event]

skb:skb_copy_datagram_iovec [Tracepoint event]

net:net_dev_xmit [Tracepoint event]

net:net_dev_queue [Tracepoint event]

net:netif_receive_skb [Tracepoint event]

net:netif_rx [Tracepoint event]

napi:napi_poll [Tracepoint event]

sock:sock_rcvqueue_full [Tracepoint event]

sock:sock_exceed_buf_limit [Tracepoint event]

udp:udp_fail_queue_rcv_skb [Tracepoint event]

hda:hda_send_cmd [Tracepoint event]

hda:hda_get_response [Tracepoint event]

hda:hda_bus_reset [Tracepoint event]

scsi:scsi_dispatch_cmd_start [Tracepoint event]

scsi:scsi_dispatch_cmd_error [Tracepoint event]

scsi:scsi_eh_wakeup [Tracepoint event]

drm:drm_vblank_event [Tracepoint event]

drm:drm_vblank_event_queued [Tracepoint event]

drm:drm_vblank_event_delivered [Tracepoint event]

random:mix_pool_bytes [Tracepoint event]

random:mix_pool_bytes_nolock [Tracepoint event]

random:credit_entropy_bits [Tracepoint event]

gpio:gpio_direction [Tracepoint event]

gpio:gpio_value [Tracepoint event]

block:block_rq_abort [Tracepoint event]

block:block_rq_requeue [Tracepoint event]

block:block_rq_issue [Tracepoint event]

block:block_bio_bounce [Tracepoint event]

block:block_bio_complete [Tracepoint event]

block:block_bio_backmerge [Tracepoint event]

.

.

writeback:writeback_wake_thread [Tracepoint event]

writeback:writeback_wake_forker_thread [Tracepoint event]

writeback:writeback_bdi_register [Tracepoint event]

.

.

writeback:writeback_single_inode_requeue [Tracepoint event]

writeback:writeback_single_inode [Tracepoint event]

kmem:kmalloc [Tracepoint event]

kmem:kmem_cache_alloc [Tracepoint event]

kmem:mm_page_alloc [Tracepoint event]

kmem:mm_page_alloc_zone_locked [Tracepoint event]

kmem:mm_page_pcpu_drain [Tracepoint event]

kmem:mm_page_alloc_extfrag [Tracepoint event]

vmscan:mm_vmscan_kswapd_sleep [Tracepoint event]

vmscan:mm_vmscan_kswapd_wake [Tracepoint event]

vmscan:mm_vmscan_wakeup_kswapd [Tracepoint event]

vmscan:mm_vmscan_direct_reclaim_begin [Tracepoint event]

.

.

module:module_get [Tracepoint event]

module:module_put [Tracepoint event]

module:module_request [Tracepoint event]

sched:sched_kthread_stop [Tracepoint event]

sched:sched_wakeup [Tracepoint event]

sched:sched_wakeup_new [Tracepoint event]

sched:sched_process_fork [Tracepoint event]

sched:sched_process_exec [Tracepoint event]

sched:sched_stat_runtime [Tracepoint event]

rcu:rcu_utilization [Tracepoint event]

workqueue:workqueue_queue_work [Tracepoint event]

workqueue:workqueue_execute_end [Tracepoint event]

signal:signal_generate [Tracepoint event]

signal:signal_deliver [Tracepoint event]

timer:timer_init [Tracepoint event]

timer:timer_start [Tracepoint event]

timer:hrtimer_cancel [Tracepoint event]

timer:itimer_state [Tracepoint event]

timer:itimer_expire [Tracepoint event]

irq:irq_handler_entry [Tracepoint event]

irq:irq_handler_exit [Tracepoint event]

irq:softirq_entry [Tracepoint event]

irq:softirq_exit [Tracepoint event]

irq:softirq_raise [Tracepoint event]

printk:console [Tracepoint event]

task:task_newtask [Tracepoint event]

task:task_rename [Tracepoint event]

syscalls:sys_enter_socketcall [Tracepoint event]

syscalls:sys_exit_socketcall [Tracepoint event]

.

.

.

syscalls:sys_enter_unshare [Tracepoint event]

syscalls:sys_exit_unshare [Tracepoint event]

raw_syscalls:sys_enter [Tracepoint event]

raw_syscalls:sys_exit [Tracepoint event]

Only a subset of these would be of interest to us when looking at this

workload, so let’s choose the most likely subsystems (identified by the

string before the colon in the Tracepoint events) and do a perf stat

run using only those subsystem wildcards:

root@crownbay:~# perf stat -e skb:* -e net:* -e napi:* -e sched:* -e workqueue:* -e irq:* -e syscalls:* wget https://downloads.yoctoproject.org/mirror/sources/linux-2.6.19.2.tar.bz2

Performance counter stats for 'wget https://downloads.yoctoproject.org/mirror/sources/linux-2.6.19.2.tar.bz2':

23323 skb:kfree_skb

0 skb:consume_skb

49897 skb:skb_copy_datagram_iovec

6217 net:net_dev_xmit

6217 net:net_dev_queue

7962 net:netif_receive_skb

2 net:netif_rx

8340 napi:napi_poll

0 sched:sched_kthread_stop

0 sched:sched_kthread_stop_ret

3749 sched:sched_wakeup

0 sched:sched_wakeup_new

0 sched:sched_switch

29 sched:sched_migrate_task

0 sched:sched_process_free

1 sched:sched_process_exit

0 sched:sched_wait_task

0 sched:sched_process_wait

0 sched:sched_process_fork

1 sched:sched_process_exec

0 sched:sched_stat_wait

2106519415641 sched:sched_stat_sleep

0 sched:sched_stat_iowait

147453613 sched:sched_stat_blocked

12903026955 sched:sched_stat_runtime

0 sched:sched_pi_setprio

3574 workqueue:workqueue_queue_work

3574 workqueue:workqueue_activate_work

0 workqueue:workqueue_execute_start

0 workqueue:workqueue_execute_end

16631 irq:irq_handler_entry

16631 irq:irq_handler_exit

28521 irq:softirq_entry

28521 irq:softirq_exit

28728 irq:softirq_raise

1 syscalls:sys_enter_sendmmsg

1 syscalls:sys_exit_sendmmsg

0 syscalls:sys_enter_recvmmsg

0 syscalls:sys_exit_recvmmsg

14 syscalls:sys_enter_socketcall

14 syscalls:sys_exit_socketcall

.

.

.

16965 syscalls:sys_enter_read

16965 syscalls:sys_exit_read

12854 syscalls:sys_enter_write

12854 syscalls:sys_exit_write

.

.

.

58.029710972 seconds time elapsed

Let’s pick one of these tracepoints and tell perf to do a profile using it as the sampling event:

root@crownbay:~# perf record -g -e sched:sched_wakeup wget https://downloads.yoctoproject.org/mirror/sources/linux-2.6.19.2.tar.bz2

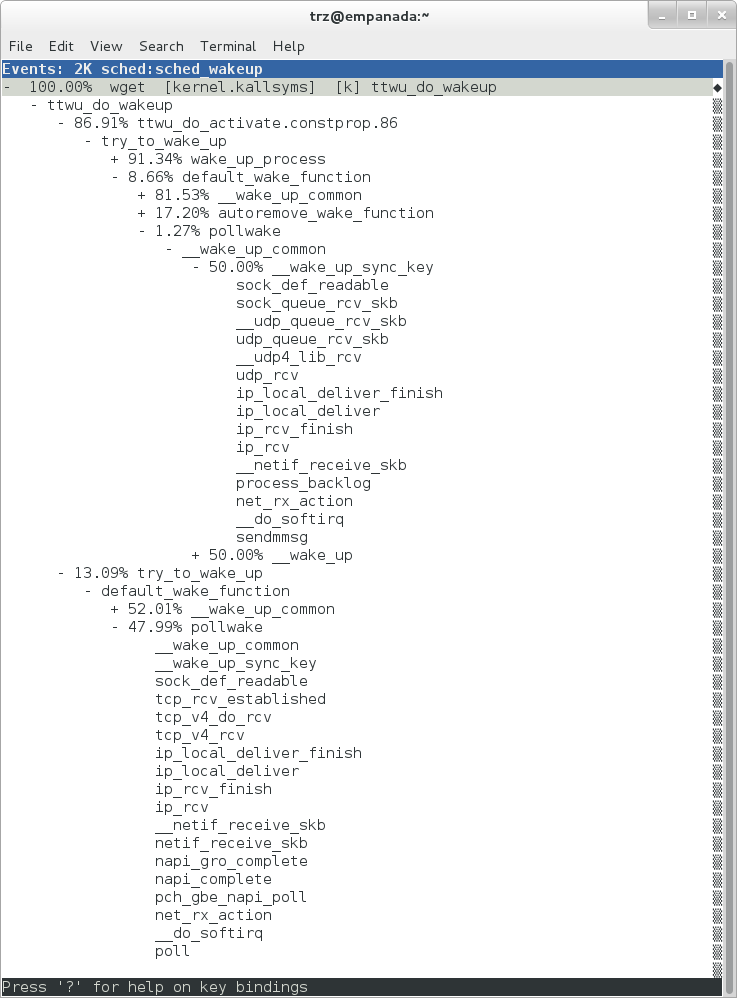

The screenshot above shows the results of running a profile using

sched:sched_switch tracepoint, which shows the relative costs of various

paths to sched_wakeup (note that sched_wakeup is the name of the

tracepoint — it’s actually defined just inside ttwu_do_wakeup(), which

accounts for the function name actually displayed in the profile:

/*

* Mark the task runnable and perform wakeup-preemption.

*/

static void

ttwu_do_wakeup(struct rq *rq, struct task_struct *p, int wake_flags)

{

trace_sched_wakeup(p, true);

.

.

.

}

A couple of the more interesting call chains are expanded and displayed above, basically some network receive paths that presumably end up waking up wget (BusyBox) when network data is ready.

Note that because tracepoints are normally used for tracing, the default

sampling period for tracepoints is 1 i.e. for tracepoints perf will

sample on every event occurrence (this can be changed using the -c

option). This is in contrast to hardware counters such as for example

the default cycles hardware counter used for normal profiling, where

sampling periods are much higher (in the thousands) because profiling

should have as low an overhead as possible and sampling on every cycle

would be prohibitively expensive.

3.1.2.2 Using perf to do Basic Tracing

Profiling is a great tool for solving many problems or for getting a

high-level view of what’s going on with a workload or across the system.

It is however by definition an approximation, as suggested by the most

prominent word associated with it, sampling. On the one hand, it

allows a representative picture of what’s going on in the system to be

cheaply taken, but alternatively, that cheapness limits its utility

when that data suggests a need to “dive down” more deeply to discover

what’s really going on. In such cases, the only way to see what’s really

going on is to be able to look at (or summarize more intelligently) the

individual steps that go into the higher-level behavior exposed by the

coarse-grained profiling data.

As a concrete example, we can trace all the events we think might be applicable to our workload:

root@crownbay:~# perf record -g -e skb:* -e net:* -e napi:* -e sched:sched_switch -e sched:sched_wakeup -e irq:*

-e syscalls:sys_enter_read -e syscalls:sys_exit_read -e syscalls:sys_enter_write -e syscalls:sys_exit_write

wget https://downloads.yoctoproject.org/mirror/sources/linux-2.6.19.2.tar.bz2

We can look at the raw trace output using perf script with no

arguments:

root@crownbay:~# perf script

perf 1262 [000] 11624.857082: sys_exit_read: 0x0

perf 1262 [000] 11624.857193: sched_wakeup: comm=migration/0 pid=6 prio=0 success=1 target_cpu=000

wget 1262 [001] 11624.858021: softirq_raise: vec=1 [action=TIMER]

wget 1262 [001] 11624.858074: softirq_entry: vec=1 [action=TIMER]

wget 1262 [001] 11624.858081: softirq_exit: vec=1 [action=TIMER]

wget 1262 [001] 11624.858166: sys_enter_read: fd: 0x0003, buf: 0xbf82c940, count: 0x0200

wget 1262 [001] 11624.858177: sys_exit_read: 0x200

wget 1262 [001] 11624.858878: kfree_skb: skbaddr=0xeb248d80 protocol=0 location=0xc15a5308

wget 1262 [001] 11624.858945: kfree_skb: skbaddr=0xeb248000 protocol=0 location=0xc15a5308

wget 1262 [001] 11624.859020: softirq_raise: vec=1 [action=TIMER]

wget 1262 [001] 11624.859076: softirq_entry: vec=1 [action=TIMER]

wget 1262 [001] 11624.859083: softirq_exit: vec=1 [action=TIMER]

wget 1262 [001] 11624.859167: sys_enter_read: fd: 0x0003, buf: 0xb7720000, count: 0x0400

wget 1262 [001] 11624.859192: sys_exit_read: 0x1d7

wget 1262 [001] 11624.859228: sys_enter_read: fd: 0x0003, buf: 0xb7720000, count: 0x0400

wget 1262 [001] 11624.859233: sys_exit_read: 0x0

wget 1262 [001] 11624.859573: sys_enter_read: fd: 0x0003, buf: 0xbf82c580, count: 0x0200

wget 1262 [001] 11624.859584: sys_exit_read: 0x200

wget 1262 [001] 11624.859864: sys_enter_read: fd: 0x0003, buf: 0xb7720000, count: 0x0400

wget 1262 [001] 11624.859888: sys_exit_read: 0x400

wget 1262 [001] 11624.859935: sys_enter_read: fd: 0x0003, buf: 0xb7720000, count: 0x0400

wget 1262 [001] 11624.859944: sys_exit_read: 0x400

This gives us a detailed timestamped sequence of events that occurred within the workload with respect to those events.

In many ways, profiling can be viewed as a subset of tracing — theoretically, if you have a set of trace events that’s sufficient to capture all the important aspects of a workload, you can derive any of the results or views that a profiling run can.

Another aspect of traditional profiling is that while powerful in many ways, it’s limited by the granularity of the underlying data. Profiling tools offer various ways of sorting and presenting the sample data, which make it much more useful and amenable to user experimentation, but in the end it can’t be used in an open-ended way to extract data that just isn’t present as a consequence of the fact that conceptually, most of it has been thrown away.

Full-blown detailed tracing data does however offer the opportunity to manipulate and present the information collected during a tracing run in an infinite variety of ways.

Another way to look at it is that there are only so many ways that the

‘primitive’ counters can be used on their own to generate interesting

output; to get anything more complicated than simple counts requires

some amount of additional logic, which is typically specific to the

problem at hand. For example, if we wanted to make use of a ‘counter’

that maps to the value of the time difference between when a process was

scheduled to run on a processor and the time it actually ran, we

wouldn’t expect such a counter to exist on its own, but we could derive

one called say wakeup_latency and use it to extract a useful view of

that metric from trace data. Likewise, we really can’t figure out from

standard profiling tools how much data every process on the system reads

and writes, along with how many of those reads and writes fail

completely. If we have sufficient trace data, however, we could with the

right tools easily extract and present that information, but we’d need

something other than ready-made profiling tools to do that.

Luckily, there is a general-purpose way to handle such needs, called “programming languages”. Making programming languages easily available to apply to such problems given the specific format of data is called a ‘programming language binding’ for that data and language. perf supports two programming language bindings, one for Python and one for Perl.

Now that we have the trace data in perf.data, we can use perf script

-g to generate a skeleton script with handlers for the read / write

entry / exit events we recorded:

root@crownbay:~# perf script -g python

generated Python script: perf-script.py

The skeleton script just creates a Python function for each event type in the

perf.data file. The body of each function just prints the event name along

with its parameters. For example:

def net__netif_rx(event_name, context, common_cpu,

common_secs, common_nsecs, common_pid, common_comm,

skbaddr, len, name):

print_header(event_name, common_cpu, common_secs, common_nsecs,

common_pid, common_comm)

print "skbaddr=%u, len=%u, name=%s\n" % (skbaddr, len, name),

We can run that script directly to print all of the events contained in the

perf.data file:

root@crownbay:~# perf script -s perf-script.py

in trace_begin

syscalls__sys_exit_read 0 11624.857082795 1262 perf nr=3, ret=0

sched__sched_wakeup 0 11624.857193498 1262 perf comm=migration/0, pid=6, prio=0, success=1, target_cpu=0

irq__softirq_raise 1 11624.858021635 1262 wget vec=TIMER

irq__softirq_entry 1 11624.858074075 1262 wget vec=TIMER

irq__softirq_exit 1 11624.858081389 1262 wget vec=TIMER

syscalls__sys_enter_read 1 11624.858166434 1262 wget nr=3, fd=3, buf=3213019456, count=512

syscalls__sys_exit_read 1 11624.858177924 1262 wget nr=3, ret=512

skb__kfree_skb 1 11624.858878188 1262 wget skbaddr=3945041280, location=3243922184, protocol=0

skb__kfree_skb 1 11624.858945608 1262 wget skbaddr=3945037824, location=3243922184, protocol=0

irq__softirq_raise 1 11624.859020942 1262 wget vec=TIMER

irq__softirq_entry 1 11624.859076935 1262 wget vec=TIMER

irq__softirq_exit 1 11624.859083469 1262 wget vec=TIMER

syscalls__sys_enter_read 1 11624.859167565 1262 wget nr=3, fd=3, buf=3077701632, count=1024

syscalls__sys_exit_read 1 11624.859192533 1262 wget nr=3, ret=471

syscalls__sys_enter_read 1 11624.859228072 1262 wget nr=3, fd=3, buf=3077701632, count=1024

syscalls__sys_exit_read 1 11624.859233707 1262 wget nr=3, ret=0

syscalls__sys_enter_read 1 11624.859573008 1262 wget nr=3, fd=3, buf=3213018496, count=512

syscalls__sys_exit_read 1 11624.859584818 1262 wget nr=3, ret=512

syscalls__sys_enter_read 1 11624.859864562 1262 wget nr=3, fd=3, buf=3077701632, count=1024

syscalls__sys_exit_read 1 11624.859888770 1262 wget nr=3, ret=1024

syscalls__sys_enter_read 1 11624.859935140 1262 wget nr=3, fd=3, buf=3077701632, count=1024

syscalls__sys_exit_read 1 11624.859944032 1262 wget nr=3, ret=1024

That in itself isn’t very useful; after all, we can accomplish pretty much the

same thing by just running perf script without arguments in the same

directory as the perf.data file.

We can however replace the print statements in the generated function bodies with whatever we want, and thereby make it infinitely more useful.

As a simple example, let’s just replace the print statements in the function bodies with a simple function that does nothing but increment a per-event count. When the program is run against a perf.data file, each time a particular event is encountered, a tally is incremented for that event. For example:

def net__netif_rx(event_name, context, common_cpu,

common_secs, common_nsecs, common_pid, common_comm,

skbaddr, len, name):

inc_counts(event_name)

Each event handler function in the generated code

is modified to do this. For convenience, we define a common function

called inc_counts() that each handler calls; inc_counts() just tallies

a count for each event using the counts hash, which is a specialized

hash function that does Perl-like autovivification, a capability that’s

extremely useful for kinds of multi-level aggregation commonly used in

processing traces (see perf’s documentation on the Python language

binding for details):

counts = autodict()

def inc_counts(event_name):

try:

counts[event_name] += 1

except TypeError:

counts[event_name] = 1

Finally, at the end of the trace processing run, we want to print the

result of all the per-event tallies. For that, we use the special

trace_end() function:

def trace_end():

for event_name, count in counts.iteritems():

print "%-40s %10s\n" % (event_name, count)

The end result is a summary of all the events recorded in the trace:

skb__skb_copy_datagram_iovec 13148

irq__softirq_entry 4796

irq__irq_handler_exit 3805

irq__softirq_exit 4795

syscalls__sys_enter_write 8990

net__net_dev_xmit 652

skb__kfree_skb 4047

sched__sched_wakeup 1155

irq__irq_handler_entry 3804

irq__softirq_raise 4799

net__net_dev_queue 652

syscalls__sys_enter_read 17599

net__netif_receive_skb 1743

syscalls__sys_exit_read 17598

net__netif_rx 2

napi__napi_poll 1877

syscalls__sys_exit_write 8990

Note that this is

pretty much exactly the same information we get from perf stat, which

goes a little way to support the idea mentioned previously that given

the right kind of trace data, higher-level profiling-type summaries can

be derived from it.

Documentation on using the ‘perf script’ python binding.

3.1.2.3 System-Wide Tracing and Profiling

The examples so far have focused on tracing a particular program or

workload — that is, every profiling run has specified the program

to profile in the command-line e.g. perf record wget ....

It’s also possible, and more interesting in many cases, to run a system-wide profile or trace while running the workload in a separate shell.

To do system-wide profiling or tracing, you typically use the -a flag to

perf record.

To demonstrate this, open up one window and start the profile using the

-a flag (press Ctrl-C to stop tracing):

root@crownbay:~# perf record -g -a

^C[ perf record: Woken up 6 times to write data ]

[ perf record: Captured and wrote 1.400 MB perf.data (~61172 samples) ]

In another window, run the wget test:

root@crownbay:~# wget https://downloads.yoctoproject.org/mirror/sources/linux-2.6.19.2.tar.bz2

Connecting to downloads.yoctoproject.org (140.211.169.59:80)

linux-2.6.19.2.tar.b 100% \|*******************************\| 41727k 0:00:00 ETA

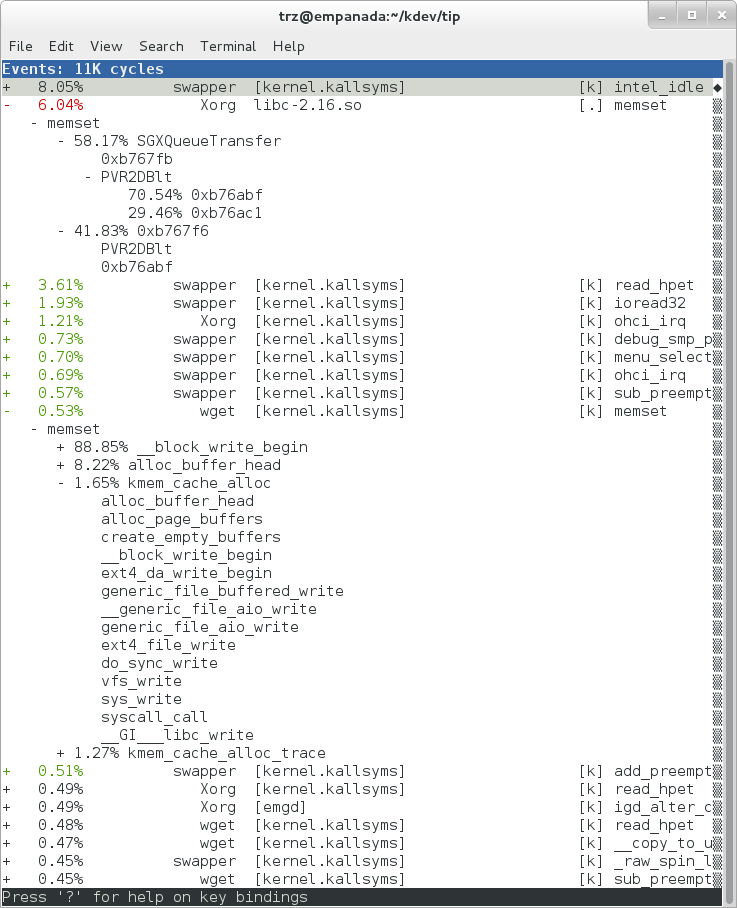

Here we see entries not only for our wget load, but for

other processes running on the system as well:

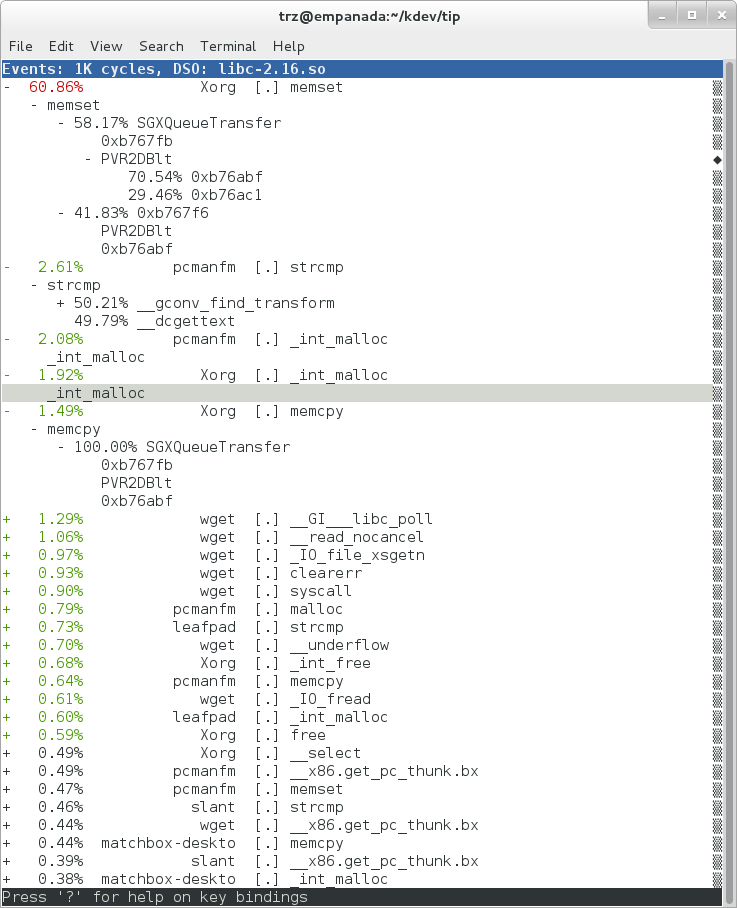

In the snapshot above, we can see call chains that originate in libc, and

a call chain from Xorg that demonstrates that we’re using a proprietary X

driver in user space (notice the presence of PVR and some other

unresolvable symbols in the expanded Xorg call chain).

Note also that we have both kernel and user space entries in the above

snapshot. We can also tell perf to focus on user space but providing a

modifier, in this case u, to the cycles hardware counter when we

record a profile:

root@crownbay:~# perf record -g -a -e cycles:u

^C[ perf record: Woken up 2 times to write data ]

[ perf record: Captured and wrote 0.376 MB perf.data (~16443 samples) ]

Notice in the screenshot above, we see only user space entries ([.])

Finally, we can press Enter on a leaf node and select the Zoom into

DSO menu item to show only entries associated with a specific DSO. In

the screenshot below, we’ve zoomed into the libc DSO which shows all

the entries associated with the libc-xxx.so DSO.

We can also use the system-wide -a switch to do system-wide tracing.

Here we’ll trace a couple of scheduler events:

root@crownbay:~# perf record -a -e sched:sched_switch -e sched:sched_wakeup

^C[ perf record: Woken up 38 times to write data ]

[ perf record: Captured and wrote 9.780 MB perf.data (~427299 samples) ]

We can look at the raw output using perf script with no arguments:

root@crownbay:~# perf script

perf 1383 [001] 6171.460045: sched_wakeup: comm=kworker/1:1 pid=21 prio=120 success=1 target_cpu=001

perf 1383 [001] 6171.460066: sched_switch: prev_comm=perf prev_pid=1383 prev_prio=120 prev_state=R+ ==> next_comm=kworker/1:1 next_pid=21 next_prio=120

kworker/1:1 21 [001] 6171.460093: sched_switch: prev_comm=kworker/1:1 prev_pid=21 prev_prio=120 prev_state=S ==> next_comm=perf next_pid=1383 next_prio=120

swapper 0 [000] 6171.468063: sched_wakeup: comm=kworker/0:3 pid=1209 prio=120 success=1 target_cpu=000

swapper 0 [000] 6171.468107: sched_switch: prev_comm=swapper/0 prev_pid=0 prev_prio=120 prev_state=R ==> next_comm=kworker/0:3 next_pid=1209 next_prio=120

kworker/0:3 1209 [000] 6171.468143: sched_switch: prev_comm=kworker/0:3 prev_pid=1209 prev_prio=120 prev_state=S ==> next_comm=swapper/0 next_pid=0 next_prio=120

perf 1383 [001] 6171.470039: sched_wakeup: comm=kworker/1:1 pid=21 prio=120 success=1 target_cpu=001

perf 1383 [001] 6171.470058: sched_switch: prev_comm=perf prev_pid=1383 prev_prio=120 prev_state=R+ ==> next_comm=kworker/1:1 next_pid=21 next_prio=120

kworker/1:1 21 [001] 6171.470082: sched_switch: prev_comm=kworker/1:1 prev_pid=21 prev_prio=120 prev_state=S ==> next_comm=perf next_pid=1383 next_prio=120

perf 1383 [001] 6171.480035: sched_wakeup: comm=kworker/1:1 pid=21 prio=120 success=1 target_cpu=001

3.1.2.3.1 Filtering

Notice that there are many events that don’t really have anything to

do with what we’re interested in, namely events that schedule perf

itself in and out or that wake perf up. We can get rid of those by using

the --filter option — for each event we specify using -e, we can add a

--filter after that to filter out trace events that contain fields with

specific values:

root@crownbay:~# perf record -a -e sched:sched_switch --filter 'next_comm != perf && prev_comm != perf' -e sched:sched_wakeup --filter 'comm != perf'

^C[ perf record: Woken up 38 times to write data ]

[ perf record: Captured and wrote 9.688 MB perf.data (~423279 samples) ]

root@crownbay:~# perf script

swapper 0 [000] 7932.162180: sched_switch: prev_comm=swapper/0 prev_pid=0 prev_prio=120 prev_state=R ==> next_comm=kworker/0:3 next_pid=1209 next_prio=120

kworker/0:3 1209 [000] 7932.162236: sched_switch: prev_comm=kworker/0:3 prev_pid=1209 prev_prio=120 prev_state=S ==> next_comm=swapper/0 next_pid=0 next_prio=120

perf 1407 [001] 7932.170048: sched_wakeup: comm=kworker/1:1 pid=21 prio=120 success=1 target_cpu=001

perf 1407 [001] 7932.180044: sched_wakeup: comm=kworker/1:1 pid=21 prio=120 success=1 target_cpu=001

perf 1407 [001] 7932.190038: sched_wakeup: comm=kworker/1:1 pid=21 prio=120 success=1 target_cpu=001

perf 1407 [001] 7932.200044: sched_wakeup: comm=kworker/1:1 pid=21 prio=120 success=1 target_cpu=001

perf 1407 [001] 7932.210044: sched_wakeup: comm=kworker/1:1 pid=21 prio=120 success=1 target_cpu=001

perf 1407 [001] 7932.220044: sched_wakeup: comm=kworker/1:1 pid=21 prio=120 success=1 target_cpu=001

swapper 0 [001] 7932.230111: sched_wakeup: comm=kworker/1:1 pid=21 prio=120 success=1 target_cpu=001

swapper 0 [001] 7932.230146: sched_switch: prev_comm=swapper/1 prev_pid=0 prev_prio=120 prev_state=R ==> next_comm=kworker/1:1 next_pid=21 next_prio=120

kworker/1:1 21 [001] 7932.230205: sched_switch: prev_comm=kworker/1:1 prev_pid=21 prev_prio=120 prev_state=S ==> next_comm=swapper/1 next_pid=0 next_prio=120

swapper 0 [000] 7932.326109: sched_wakeup: comm=kworker/0:3 pid=1209 prio=120 success=1 target_cpu=000

swapper 0 [000] 7932.326171: sched_switch: prev_comm=swapper/0 prev_pid=0 prev_prio=120 prev_state=R ==> next_comm=kworker/0:3 next_pid=1209 next_prio=120

kworker/0:3 1209 [000] 7932.326214: sched_switch: prev_comm=kworker/0:3 prev_pid=1209 prev_prio=120 prev_state=S ==> next_comm=swapper/0 next_pid=0 next_prio=120

In this case, we’ve filtered out all events that have

perf in their comm, comm_prev or comm_next fields. Notice that

there are still events recorded for perf, but notice that those events

don’t have values of perf for the filtered fields. To completely

filter out anything from perf will require a bit more work, but for the

purpose of demonstrating how to use filters, it’s close enough.

3.1.2.4 Using Dynamic Tracepoints

perf isn’t restricted to the fixed set of static tracepoints listed by

perf list. Users can also add their own “dynamic” tracepoints anywhere

in the kernel. For example, suppose we want to define our own

tracepoint on do_fork(). We can do that using the perf probe perf

subcommand:

root@crownbay:~# perf probe do_fork

Added new event:

probe:do_fork (on do_fork)

You can now use it in all perf tools, such as:

perf record -e probe:do_fork -aR sleep 1

Adding a new tracepoint via

perf probe results in an event with all the expected files and format

in /sys/kernel/debug/tracing/events, just the same as for static

tracepoints (as discussed in more detail in the trace events subsystem

section:

root@crownbay:/sys/kernel/debug/tracing/events/probe/do_fork# ls -al

drwxr-xr-x 2 root root 0 Oct 28 11:42 .

drwxr-xr-x 3 root root 0 Oct 28 11:42 ..

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 0 Oct 28 11:42 enable

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 0 Oct 28 11:42 filter

-r--r--r-- 1 root root 0 Oct 28 11:42 format

-r--r--r-- 1 root root 0 Oct 28 11:42 id

root@crownbay:/sys/kernel/debug/tracing/events/probe/do_fork# cat format

name: do_fork

ID: 944

format:

field:unsigned short common_type; offset:0; size:2; signed:0;

field:unsigned char common_flags; offset:2; size:1; signed:0;

field:unsigned char common_preempt_count; offset:3; size:1; signed:0;

field:int common_pid; offset:4; size:4; signed:1;

field:int common_padding; offset:8; size:4; signed:1;

field:unsigned long __probe_ip; offset:12; size:4; signed:0;

print fmt: "(%lx)", REC->__probe_ip

We can list all dynamic tracepoints currently in existence:

root@crownbay:~# perf probe -l

probe:do_fork (on do_fork)

probe:schedule (on schedule)

Let’s record system-wide (sleep 30 is a

trick for recording system-wide but basically do nothing and then wake

up after 30 seconds):

root@crownbay:~# perf record -g -a -e probe:do_fork sleep 30

[ perf record: Woken up 1 times to write data ]

[ perf record: Captured and wrote 0.087 MB perf.data (~3812 samples) ]

Using perf script we can see each do_fork event that fired:

root@crownbay:~# perf script

# ========

# captured on: Sun Oct 28 11:55:18 2012

# hostname : crownbay

# os release : 3.4.11-yocto-standard

# perf version : 3.4.11

# arch : i686

# nrcpus online : 2

# nrcpus avail : 2

# cpudesc : Intel(R) Atom(TM) CPU E660 @ 1.30GHz

# cpuid : GenuineIntel,6,38,1

# total memory : 1017184 kB

# cmdline : /usr/bin/perf record -g -a -e probe:do_fork sleep 30

# event : name = probe:do_fork, type = 2, config = 0x3b0, config1 = 0x0, config2 = 0x0, excl_usr = 0, excl_kern

= 0, id = { 5, 6 }

# HEADER_CPU_TOPOLOGY info available, use -I to display

# ========

#

matchbox-deskto 1197 [001] 34211.378318: do_fork: (c1028460)

matchbox-deskto 1295 [001] 34211.380388: do_fork: (c1028460)

pcmanfm 1296 [000] 34211.632350: do_fork: (c1028460)

pcmanfm 1296 [000] 34211.639917: do_fork: (c1028460)

matchbox-deskto 1197 [001] 34217.541603: do_fork: (c1028460)

matchbox-deskto 1299 [001] 34217.543584: do_fork: (c1028460)

gthumb 1300 [001] 34217.697451: do_fork: (c1028460)

gthumb 1300 [001] 34219.085734: do_fork: (c1028460)

gthumb 1300 [000] 34219.121351: do_fork: (c1028460)

gthumb 1300 [001] 34219.264551: do_fork: (c1028460)

pcmanfm 1296 [000] 34219.590380: do_fork: (c1028460)

matchbox-deskto 1197 [001] 34224.955965: do_fork: (c1028460)

matchbox-deskto 1306 [001] 34224.957972: do_fork: (c1028460)

matchbox-termin 1307 [000] 34225.038214: do_fork: (c1028460)

matchbox-termin 1307 [001] 34225.044218: do_fork: (c1028460)

matchbox-termin 1307 [000] 34225.046442: do_fork: (c1028460)

matchbox-deskto 1197 [001] 34237.112138: do_fork: (c1028460)

matchbox-deskto 1311 [001] 34237.114106: do_fork: (c1028460)

gaku 1312 [000] 34237.202388: do_fork: (c1028460)

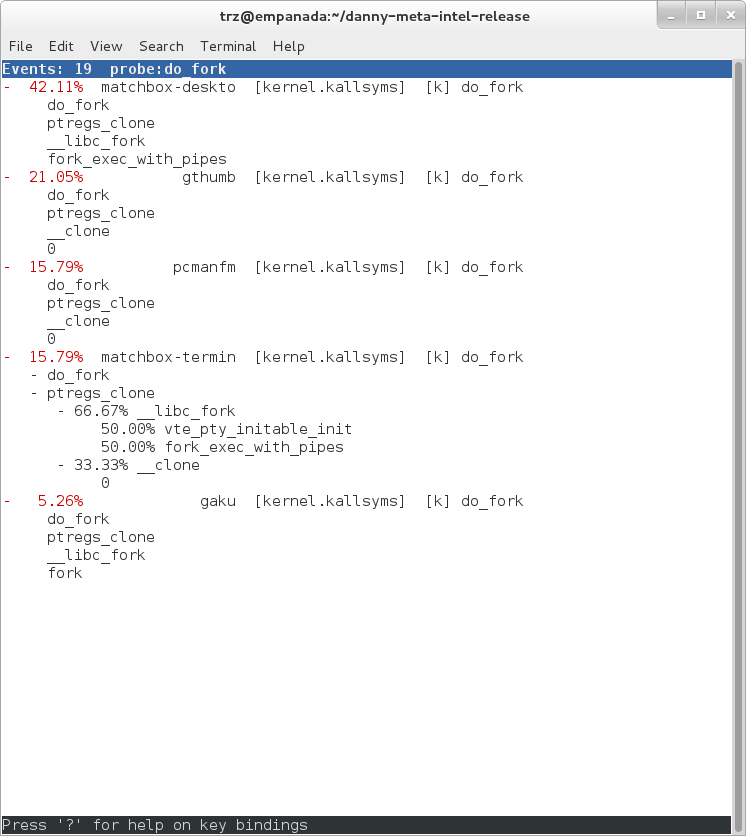

And using perf report on the same file, we can see the

call graphs from starting a few programs during those 30 seconds:

3.1.3 perf Documentation

Online versions of the manual pages for the commands discussed in this section can be found here:

Documentation on using the ‘perf script’ python binding.

The top-level perf(1) manual page.

Normally, you should be able to open the manual pages via perf itself

e.g. perf help or perf help record.

To have the perf manual pages installed on your target, modify your configuration as follows:

IMAGE_INSTALL:append = " perf perf-doc"

DISTRO_FEATURES:append = " api-documentation"

The manual pages in text form, along with some other files, such as a set

of examples, can also be found in the perf directory of the kernel tree:

tools/perf/Documentation

There’s also a nice perf tutorial on the perf wiki that goes into more detail than we do here in certain areas: perf Tutorial

3.2 ftrace

“ftrace” literally refers to the “ftrace function tracer” but in reality this encompasses several related tracers along with the infrastructure that they all make use of.

3.2.1 ftrace Setup

For this section, we’ll assume you’ve already performed the basic setup outlined in the “General Setup” section.

ftrace, trace-cmd, and KernelShark run on the target system, and are

ready to go out-of-the-box — no additional setup is necessary. For the

rest of this section we assume you’re connected to the host through SSH and

will be running ftrace on the target. KernelShark is a GUI application and if

you use the -X option to ssh you can have the KernelShark GUI run on

the target but display remotely on the host if you want.

3.2.2 Basic ftrace usage

“ftrace” essentially refers to everything included in the /tracing

directory of the mounted debugfs filesystem (Yocto follows the standard

convention and mounts it at /sys/kernel/debug). All the files found in

/sys/kernel/debug/tracing on a Yocto system are:

root@sugarbay:/sys/kernel/debug/tracing# ls

README kprobe_events trace

available_events kprobe_profile trace_clock

available_filter_functions options trace_marker

available_tracers per_cpu trace_options

buffer_size_kb printk_formats trace_pipe

buffer_total_size_kb saved_cmdlines tracing_cpumask

current_tracer set_event tracing_enabled

dyn_ftrace_total_info set_ftrace_filter tracing_on

enabled_functions set_ftrace_notrace tracing_thresh

events set_ftrace_pid

free_buffer set_graph_function

The files listed above are used for various purposes — some relate directly to the tracers themselves, others are used to set tracing options, and yet others actually contain the tracing output when a tracer is in effect. Some of the functions can be guessed from their names, others need explanation; in any case, we’ll cover some of the files we see here below but for an explanation of the others, please see the ftrace documentation.

We’ll start by looking at some of the available built-in tracers.

The available_tracers file lists the set of available tracers:

root@sugarbay:/sys/kernel/debug/tracing# cat available_tracers

blk function_graph function nop

The current_tracer file contains the tracer currently in effect:

root@sugarbay:/sys/kernel/debug/tracing# cat current_tracer

nop

The above listing of current_tracer shows that the

nop tracer is in effect, which is just another way of saying that

there’s actually no tracer currently in effect.

Writing one of the available tracers into current_tracer makes the

specified tracer the current tracer:

root@sugarbay:/sys/kernel/debug/tracing# echo function > current_tracer

root@sugarbay:/sys/kernel/debug/tracing# cat current_tracer

function

The above sets the current tracer to be the function tracer. This tracer

traces every function call in the kernel and makes it available as the

contents of the trace file. Reading the trace file lists the

currently buffered function calls that have been traced by the function

tracer:

root@sugarbay:/sys/kernel/debug/tracing# cat trace | less

# tracer: function

#

# entries-in-buffer/entries-written: 310629/766471 #P:8

#

# _-----=> irqs-off

# / _----=> need-resched

# | / _---=> hardirq/softirq

# || / _--=> preempt-depth

# ||| / delay

# TASK-PID CPU# |||| TIMESTAMP FUNCTION

# | | | |||| | |

<idle>-0 [004] d..1 470.867169: ktime_get_real <-intel_idle

<idle>-0 [004] d..1 470.867170: getnstimeofday <-ktime_get_real

<idle>-0 [004] d..1 470.867171: ns_to_timeval <-intel_idle

<idle>-0 [004] d..1 470.867171: ns_to_timespec <-ns_to_timeval

<idle>-0 [004] d..1 470.867172: smp_apic_timer_interrupt <-apic_timer_interrupt

<idle>-0 [004] d..1 470.867172: native_apic_mem_write <-smp_apic_timer_interrupt

<idle>-0 [004] d..1 470.867172: irq_enter <-smp_apic_timer_interrupt

<idle>-0 [004] d..1 470.867172: rcu_irq_enter <-irq_enter

<idle>-0 [004] d..1 470.867173: rcu_idle_exit_common.isra.33 <-rcu_irq_enter

<idle>-0 [004] d..1 470.867173: local_bh_disable <-irq_enter

<idle>-0 [004] d..1 470.867173: add_preempt_count <-local_bh_disable

<idle>-0 [004] d.s1 470.867174: tick_check_idle <-irq_enter

<idle>-0 [004] d.s1 470.867174: tick_check_oneshot_broadcast <-tick_check_idle

<idle>-0 [004] d.s1 470.867174: ktime_get <-tick_check_idle

<idle>-0 [004] d.s1 470.867174: tick_nohz_stop_idle <-tick_check_idle

<idle>-0 [004] d.s1 470.867175: update_ts_time_stats <-tick_nohz_stop_idle

<idle>-0 [004] d.s1 470.867175: nr_iowait_cpu <-update_ts_time_stats

<idle>-0 [004] d.s1 470.867175: tick_do_update_jiffies64 <-tick_check_idle

<idle>-0 [004] d.s1 470.867175: _raw_spin_lock <-tick_do_update_jiffies64

<idle>-0 [004] d.s1 470.867176: add_preempt_count <-_raw_spin_lock

<idle>-0 [004] d.s2 470.867176: do_timer <-tick_do_update_jiffies64

<idle>-0 [004] d.s2 470.867176: _raw_spin_lock <-do_timer

<idle>-0 [004] d.s2 470.867176: add_preempt_count <-_raw_spin_lock

<idle>-0 [004] d.s3 470.867177: ntp_tick_length <-do_timer

<idle>-0 [004] d.s3 470.867177: _raw_spin_lock_irqsave <-ntp_tick_length

.

.

.

Each line in the trace above shows what was happening in the kernel on a given CPU, to the level of detail of function calls. Each entry shows the function called, followed by its caller (after the arrow).

The function tracer gives you an extremely detailed idea of what the kernel was doing at the point in time the trace was taken, and is a great way to learn about how the kernel code works in a dynamic sense.

It is a little more difficult to follow the call chains than it needs to

be — luckily there’s a variant of the function tracer that displays the

call chains explicitly, called the function_graph tracer:

root@sugarbay:/sys/kernel/debug/tracing# echo function_graph > current_tracer

root@sugarbay:/sys/kernel/debug/tracing# cat trace | less

tracer: function_graph

CPU DURATION FUNCTION CALLS

| | | | | | |

7) 0.046 us | pick_next_task_fair();

7) 0.043 us | pick_next_task_stop();

7) 0.042 us | pick_next_task_rt();

7) 0.032 us | pick_next_task_fair();

7) 0.030 us | pick_next_task_idle();

7) | _raw_spin_unlock_irq() {

7) 0.033 us | sub_preempt_count();

7) 0.258 us | }

7) 0.032 us | sub_preempt_count();

7) + 13.341 us | } /* __schedule */

7) 0.095 us | } /* sub_preempt_count */

7) | schedule() {

7) | __schedule() {

7) 0.060 us | add_preempt_count();

7) 0.044 us | rcu_note_context_switch();

7) | _raw_spin_lock_irq() {

7) 0.033 us | add_preempt_count();

7) 0.247 us | }

7) | idle_balance() {

7) | _raw_spin_unlock() {

7) 0.031 us | sub_preempt_count();

7) 0.246 us | }

7) | update_shares() {

7) 0.030 us | __rcu_read_lock();

7) 0.029 us | __rcu_read_unlock();

7) 0.484 us | }

7) 0.030 us | __rcu_read_lock();

7) | load_balance() {

7) | find_busiest_group() {

7) 0.031 us | idle_cpu();

7) 0.029 us | idle_cpu();

7) 0.035 us | idle_cpu();

7) 0.906 us | }

7) 1.141 us | }

7) 0.022 us | msecs_to_jiffies();

7) | load_balance() {

7) | find_busiest_group() {

7) 0.031 us | idle_cpu();

.

.

.

4) 0.062 us | msecs_to_jiffies();

4) 0.062 us | __rcu_read_unlock();

4) | _raw_spin_lock() {

4) 0.073 us | add_preempt_count();

4) 0.562 us | }

4) + 17.452 us | }

4) 0.108 us | put_prev_task_fair();

4) 0.102 us | pick_next_task_fair();

4) 0.084 us | pick_next_task_stop();

4) 0.075 us | pick_next_task_rt();

4) 0.062 us | pick_next_task_fair();

4) 0.066 us | pick_next_task_idle();

------------------------------------------

4) kworker-74 => <idle>-0

------------------------------------------

4) | finish_task_switch() {

4) | _raw_spin_unlock_irq() {

4) 0.100 us | sub_preempt_count();

4) 0.582 us | }

4) 1.105 us | }

4) 0.088 us | sub_preempt_count();

4) ! 100.066 us | }

.

.

.

3) | sys_ioctl() {

3) 0.083 us | fget_light();

3) | security_file_ioctl() {

3) 0.066 us | cap_file_ioctl();

3) 0.562 us | }

3) | do_vfs_ioctl() {

3) | drm_ioctl() {

3) 0.075 us | drm_ut_debug_printk();

3) | i915_gem_pwrite_ioctl() {

3) | i915_mutex_lock_interruptible() {

3) 0.070 us | mutex_lock_interruptible();

3) 0.570 us | }

3) | drm_gem_object_lookup() {

3) | _raw_spin_lock() {

3) 0.080 us | add_preempt_count();

3) 0.620 us | }

3) | _raw_spin_unlock() {

3) 0.085 us | sub_preempt_count();

3) 0.562 us | }

3) 2.149 us | }

3) 0.133 us | i915_gem_object_pin();

3) | i915_gem_object_set_to_gtt_domain() {

3) 0.065 us | i915_gem_object_flush_gpu_write_domain();

3) 0.065 us | i915_gem_object_wait_rendering();

3) 0.062 us | i915_gem_object_flush_cpu_write_domain();

3) 1.612 us | }

3) | i915_gem_object_put_fence() {

3) 0.097 us | i915_gem_object_flush_fence.constprop.36();

3) 0.645 us | }

3) 0.070 us | add_preempt_count();

3) 0.070 us | sub_preempt_count();

3) 0.073 us | i915_gem_object_unpin();

3) 0.068 us | mutex_unlock();

3) 9.924 us | }

3) + 11.236 us | }

3) + 11.770 us | }

3) + 13.784 us | }

3) | sys_ioctl() {

As you can see, the function_graph display is much easier

to follow. Also note that in addition to the function calls and

associated braces, other events such as scheduler events are displayed

in context. In fact, you can freely include any tracepoint available in

the trace events subsystem described in the next section by just

enabling those events, and they’ll appear in context in the function

graph display. Quite a powerful tool for understanding kernel dynamics.

Also notice that there are various annotations on the left hand side of the display. For example if the total time it took for a given function to execute is above a certain threshold, an exclamation point or plus sign appears on the left hand side. Please see the ftrace documentation for details on all these fields.

3.2.3 The ‘trace events’ Subsystem

One especially important directory contained within the

/sys/kernel/debug/tracing directory is the events subdirectory, which

contains representations of every tracepoint in the system. Listing out

the contents of the events subdirectory, we see mainly another set of

subdirectories:

root@sugarbay:/sys/kernel/debug/tracing# cd events

root@sugarbay:/sys/kernel/debug/tracing/events# ls -al

drwxr-xr-x 38 root root 0 Nov 14 23:19 .

drwxr-xr-x 5 root root 0 Nov 14 23:19 ..

drwxr-xr-x 19 root root 0 Nov 14 23:19 block

drwxr-xr-x 32 root root 0 Nov 14 23:19 btrfs

drwxr-xr-x 5 root root 0 Nov 14 23:19 drm

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 0 Nov 14 23:19 enable

drwxr-xr-x 40 root root 0 Nov 14 23:19 ext3

drwxr-xr-x 79 root root 0 Nov 14 23:19 ext4

drwxr-xr-x 14 root root 0 Nov 14 23:19 ftrace

drwxr-xr-x 8 root root 0 Nov 14 23:19 hda

-r--r--r-- 1 root root 0 Nov 14 23:19 header_event

-r--r--r-- 1 root root 0 Nov 14 23:19 header_page

drwxr-xr-x 25 root root 0 Nov 14 23:19 i915

drwxr-xr-x 7 root root 0 Nov 14 23:19 irq

drwxr-xr-x 12 root root 0 Nov 14 23:19 jbd

drwxr-xr-x 14 root root 0 Nov 14 23:19 jbd2

drwxr-xr-x 14 root root 0 Nov 14 23:19 kmem

drwxr-xr-x 7 root root 0 Nov 14 23:19 module

drwxr-xr-x 3 root root 0 Nov 14 23:19 napi

drwxr-xr-x 6 root root 0 Nov 14 23:19 net

drwxr-xr-x 3 root root 0 Nov 14 23:19 oom

drwxr-xr-x 12 root root 0 Nov 14 23:19 power

drwxr-xr-x 3 root root 0 Nov 14 23:19 printk

drwxr-xr-x 8 root root 0 Nov 14 23:19 random

drwxr-xr-x 4 root root 0 Nov 14 23:19 raw_syscalls

drwxr-xr-x 3 root root 0 Nov 14 23:19 rcu

drwxr-xr-x 6 root root 0 Nov 14 23:19 rpm

drwxr-xr-x 20 root root 0 Nov 14 23:19 sched

drwxr-xr-x 7 root root 0 Nov 14 23:19 scsi

drwxr-xr-x 4 root root 0 Nov 14 23:19 signal

drwxr-xr-x 5 root root 0 Nov 14 23:19 skb

drwxr-xr-x 4 root root 0 Nov 14 23:19 sock

drwxr-xr-x 10 root root 0 Nov 14 23:19 sunrpc

drwxr-xr-x 538 root root 0 Nov 14 23:19 syscalls

drwxr-xr-x 4 root root 0 Nov 14 23:19 task

drwxr-xr-x 14 root root 0 Nov 14 23:19 timer

drwxr-xr-x 3 root root 0 Nov 14 23:19 udp

drwxr-xr-x 21 root root 0 Nov 14 23:19 vmscan

drwxr-xr-x 3 root root 0 Nov 14 23:19 vsyscall

drwxr-xr-x 6 root root 0 Nov 14 23:19 workqueue

drwxr-xr-x 26 root root 0 Nov 14 23:19 writeback

Each one of these subdirectories

corresponds to a “subsystem” and contains yet again more subdirectories,

each one of those finally corresponding to a tracepoint. For example,

here are the contents of the kmem subsystem:

root@sugarbay:/sys/kernel/debug/tracing/events# cd kmem

root@sugarbay:/sys/kernel/debug/tracing/events/kmem# ls -al

drwxr-xr-x 14 root root 0 Nov 14 23:19 .

drwxr-xr-x 38 root root 0 Nov 14 23:19 ..

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 0 Nov 14 23:19 enable

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 0 Nov 14 23:19 filter

drwxr-xr-x 2 root root 0 Nov 14 23:19 kfree

drwxr-xr-x 2 root root 0 Nov 14 23:19 kmalloc

drwxr-xr-x 2 root root 0 Nov 14 23:19 kmalloc_node

drwxr-xr-x 2 root root 0 Nov 14 23:19 kmem_cache_alloc

drwxr-xr-x 2 root root 0 Nov 14 23:19 kmem_cache_alloc_node

drwxr-xr-x 2 root root 0 Nov 14 23:19 kmem_cache_free

drwxr-xr-x 2 root root 0 Nov 14 23:19 mm_page_alloc

drwxr-xr-x 2 root root 0 Nov 14 23:19 mm_page_alloc_extfrag

drwxr-xr-x 2 root root 0 Nov 14 23:19 mm_page_alloc_zone_locked

drwxr-xr-x 2 root root 0 Nov 14 23:19 mm_page_free

drwxr-xr-x 2 root root 0 Nov 14 23:19 mm_page_free_batched

drwxr-xr-x 2 root root 0 Nov 14 23:19 mm_page_pcpu_drain

Let’s see what’s inside the subdirectory for a

specific tracepoint, in this case the one for kmalloc:

root@sugarbay:/sys/kernel/debug/tracing/events/kmem# cd kmalloc

root@sugarbay:/sys/kernel/debug/tracing/events/kmem/kmalloc# ls -al

drwxr-xr-x 2 root root 0 Nov 14 23:19 .

drwxr-xr-x 14 root root 0 Nov 14 23:19 ..

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 0 Nov 14 23:19 enable

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 0 Nov 14 23:19 filter

-r--r--r-- 1 root root 0 Nov 14 23:19 format

-r--r--r-- 1 root root 0 Nov 14 23:19 id

The format file for the

tracepoint describes the event in memory, which is used by the various

tracing tools that now make use of these tracepoint to parse the event

and make sense of it, along with a print fmt field that allows tools

like ftrace to display the event as text. The format of the

kmalloc event looks like:

root@sugarbay:/sys/kernel/debug/tracing/events/kmem/kmalloc# cat format

name: kmalloc

ID: 313

format:

field:unsigned short common_type; offset:0; size:2; signed:0;

field:unsigned char common_flags; offset:2; size:1; signed:0;

field:unsigned char common_preempt_count; offset:3; size:1; signed:0;

field:int common_pid; offset:4; size:4; signed:1;

field:int common_padding; offset:8; size:4; signed:1;

field:unsigned long call_site; offset:16; size:8; signed:0;

field:const void * ptr; offset:24; size:8; signed:0;

field:size_t bytes_req; offset:32; size:8; signed:0;

field:size_t bytes_alloc; offset:40; size:8; signed:0;

field:gfp_t gfp_flags; offset:48; size:4; signed:0;

print fmt: "call_site=%lx ptr=%p bytes_req=%zu bytes_alloc=%zu gfp_flags=%s", REC->call_site, REC->ptr, REC->bytes_req, REC->bytes_alloc,

(REC->gfp_flags) ? __print_flags(REC->gfp_flags, "|", {(unsigned long)(((( gfp_t)0x10u) | (( gfp_t)0x40u) | (( gfp_t)0x80u) | ((

gfp_t)0x20000u) | (( gfp_t)0x02u) | (( gfp_t)0x08u)) | (( gfp_t)0x4000u) | (( gfp_t)0x10000u) | (( gfp_t)0x1000u) | (( gfp_t)0x200u) | ((

gfp_t)0x400000u)), "GFP_TRANSHUGE"}, {(unsigned long)((( gfp_t)0x10u) | (( gfp_t)0x40u) | (( gfp_t)0x80u) | (( gfp_t)0x20000u) | ((

gfp_t)0x02u) | (( gfp_t)0x08u)), "GFP_HIGHUSER_MOVABLE"}, {(unsigned long)((( gfp_t)0x10u) | (( gfp_t)0x40u) | (( gfp_t)0x80u) | ((

gfp_t)0x20000u) | (( gfp_t)0x02u)), "GFP_HIGHUSER"}, {(unsigned long)((( gfp_t)0x10u) | (( gfp_t)0x40u) | (( gfp_t)0x80u) | ((

gfp_t)0x20000u)), "GFP_USER"}, {(unsigned long)((( gfp_t)0x10u) | (( gfp_t)0x40u) | (( gfp_t)0x80u) | (( gfp_t)0x80000u)), GFP_TEMPORARY"},

{(unsigned long)((( gfp_t)0x10u) | (( gfp_t)0x40u) | (( gfp_t)0x80u)), "GFP_KERNEL"}, {(unsigned long)((( gfp_t)0x10u) | (( gfp_t)0x40u)),

"GFP_NOFS"}, {(unsigned long)((( gfp_t)0x20u)), "GFP_ATOMIC"}, {(unsigned long)((( gfp_t)0x10u)), "GFP_NOIO"}, {(unsigned long)((

gfp_t)0x20u), "GFP_HIGH"}, {(unsigned long)(( gfp_t)0x10u), "GFP_WAIT"}, {(unsigned long)(( gfp_t)0x40u), "GFP_IO"}, {(unsigned long)((

gfp_t)0x100u), "GFP_COLD"}, {(unsigned long)(( gfp_t)0x200u), "GFP_NOWARN"}, {(unsigned long)(( gfp_t)0x400u), "GFP_REPEAT"}, {(unsigned

long)(( gfp_t)0x800u), "GFP_NOFAIL"}, {(unsigned long)(( gfp_t)0x1000u), "GFP_NORETRY"}, {(unsigned long)(( gfp_t)0x4000u), "GFP_COMP"},

{(unsigned long)(( gfp_t)0x8000u), "GFP_ZERO"}, {(unsigned long)(( gfp_t)0x10000u), "GFP_NOMEMALLOC"}, {(unsigned long)(( gfp_t)0x20000u),

"GFP_HARDWALL"}, {(unsigned long)(( gfp_t)0x40000u), "GFP_THISNODE"}, {(unsigned long)(( gfp_t)0x80000u), "GFP_RECLAIMABLE"}, {(unsigned

long)(( gfp_t)0x08u), "GFP_MOVABLE"}, {(unsigned long)(( gfp_t)0), "GFP_NOTRACK"}, {(unsigned long)(( gfp_t)0x400000u), "GFP_NO_KSWAPD"},

{(unsigned long)(( gfp_t)0x800000u), "GFP_OTHER_NODE"} ) : "GFP_NOWAIT"

The enable file

in the tracepoint directory is what allows the user (or tools such as

trace-cmd) to actually turn the tracepoint on and off. When enabled, the

corresponding tracepoint will start appearing in the ftrace trace file

described previously. For example, this turns on the kmalloc tracepoint:

root@sugarbay:/sys/kernel/debug/tracing/events/kmem/kmalloc# echo 1 > enable

At the moment, we’re not interested in the function tracer or some other tracer that might be in effect, so we first turn it off, but if we do that, we still need to turn tracing on in order to see the events in the output buffer:

root@sugarbay:/sys/kernel/debug/tracing# echo nop > current_tracer

root@sugarbay:/sys/kernel/debug/tracing# echo 1 > tracing_on

Now, if we look at the trace file, we see nothing

but the kmalloc events we just turned on:

root@sugarbay:/sys/kernel/debug/tracing# cat trace | less

# tracer: nop

#

# entries-in-buffer/entries-written: 1897/1897 #P:8

#

# _-----=> irqs-off

# / _----=> need-resched

# | / _---=> hardirq/softirq

# || / _--=> preempt-depth

# ||| / delay

# TASK-PID CPU# |||| TIMESTAMP FUNCTION

# | | | |||| | |

dropbear-1465 [000] ...1 18154.620753: kmalloc: call_site=ffffffff816650d4 ptr=ffff8800729c3000 bytes_req=2048 bytes_alloc=2048 gfp_flags=GFP_KERNEL

<idle>-0 [000] ..s3 18154.621640: kmalloc: call_site=ffffffff81619b36 ptr=ffff88006d555800 bytes_req=512 bytes_alloc=512 gfp_flags=GFP_ATOMIC

<idle>-0 [000] ..s3 18154.621656: kmalloc: call_site=ffffffff81619b36 ptr=ffff88006d555800 bytes_req=512 bytes_alloc=512 gfp_flags=GFP_ATOMIC

matchbox-termin-1361 [001] ...1 18154.755472: kmalloc: call_site=ffffffff81614050 ptr=ffff88006d5f0e00 bytes_req=512 bytes_alloc=512 gfp_flags=GFP_KERNEL|GFP_REPEAT

Xorg-1264 [002] ...1 18154.755581: kmalloc: call_site=ffffffff8141abe8 ptr=ffff8800734f4cc0 bytes_req=168 bytes_alloc=192 gfp_flags=GFP_KERNEL|GFP_NOWARN|GFP_NORETRY

Xorg-1264 [002] ...1 18154.755583: kmalloc: call_site=ffffffff814192a3 ptr=ffff88001f822520 bytes_req=24 bytes_alloc=32 gfp_flags=GFP_KERNEL|GFP_ZERO

Xorg-1264 [002] ...1 18154.755589: kmalloc: call_site=ffffffff81419edb ptr=ffff8800721a2f00 bytes_req=64 bytes_alloc=64 gfp_flags=GFP_KERNEL|GFP_ZERO

matchbox-termin-1361 [001] ...1 18155.354594: kmalloc: call_site=ffffffff81614050 ptr=ffff88006db35400 bytes_req=576 bytes_alloc=1024 gfp_flags=GFP_KERNEL|GFP_REPEAT

Xorg-1264 [002] ...1 18155.354703: kmalloc: call_site=ffffffff8141abe8 ptr=ffff8800734f4cc0 bytes_req=168 bytes_alloc=192 gfp_flags=GFP_KERNEL|GFP_NOWARN|GFP_NORETRY

Xorg-1264 [002] ...1 18155.354705: kmalloc: call_site=ffffffff814192a3 ptr=ffff88001f822520 bytes_req=24 bytes_alloc=32 gfp_flags=GFP_KERNEL|GFP_ZERO

Xorg-1264 [002] ...1 18155.354711: kmalloc: call_site=ffffffff81419edb ptr=ffff8800721a2f00 bytes_req=64 bytes_alloc=64 gfp_flags=GFP_KERNEL|GFP_ZERO

<idle>-0 [000] ..s3 18155.673319: kmalloc: call_site=ffffffff81619b36 ptr=ffff88006d555800 bytes_req=512 bytes_alloc=512 gfp_flags=GFP_ATOMIC

dropbear-1465 [000] ...1 18155.673525: kmalloc: call_site=ffffffff816650d4 ptr=ffff8800729c3000 bytes_req=2048 bytes_alloc=2048 gfp_flags=GFP_KERNEL

<idle>-0 [000] ..s3 18155.674821: kmalloc: call_site=ffffffff81619b36 ptr=ffff88006d554800 bytes_req=512 bytes_alloc=512 gfp_flags=GFP_ATOMIC

<idle>-0 [000] ..s3 18155.793014: kmalloc: call_site=ffffffff81619b36 ptr=ffff88006d554800 bytes_req=512 bytes_alloc=512 gfp_flags=GFP_ATOMIC

dropbear-1465 [000] ...1 18155.793219: kmalloc: call_site=ffffffff816650d4 ptr=ffff8800729c3000 bytes_req=2048 bytes_alloc=2048 gfp_flags=GFP_KERNEL

<idle>-0 [000] ..s3 18155.794147: kmalloc: call_site=ffffffff81619b36 ptr=ffff88006d555800 bytes_req=512 bytes_alloc=512 gfp_flags=GFP_ATOMIC

<idle>-0 [000] ..s3 18155.936705: kmalloc: call_site=ffffffff81619b36 ptr=ffff88006d555800 bytes_req=512 bytes_alloc=512 gfp_flags=GFP_ATOMIC

dropbear-1465 [000] ...1 18155.936910: kmalloc: call_site=ffffffff816650d4 ptr=ffff8800729c3000 bytes_req=2048 bytes_alloc=2048 gfp_flags=GFP_KERNEL

<idle>-0 [000] ..s3 18155.937869: kmalloc: call_site=ffffffff81619b36 ptr=ffff88006d554800 bytes_req=512 bytes_alloc=512 gfp_flags=GFP_ATOMIC

matchbox-termin-1361 [001] ...1 18155.953667: kmalloc: call_site=ffffffff81614050 ptr=ffff88006d5f2000 bytes_req=512 bytes_alloc=512 gfp_flags=GFP_KERNEL|GFP_REPEAT

Xorg-1264 [002] ...1 18155.953775: kmalloc: call_site=ffffffff8141abe8 ptr=ffff8800734f4cc0 bytes_req=168 bytes_alloc=192 gfp_flags=GFP_KERNEL|GFP_NOWARN|GFP_NORETRY

Xorg-1264 [002] ...1 18155.953777: kmalloc: call_site=ffffffff814192a3 ptr=ffff88001f822520 bytes_req=24 bytes_alloc=32 gfp_flags=GFP_KERNEL|GFP_ZERO

Xorg-1264 [002] ...1 18155.953783: kmalloc: call_site=ffffffff81419edb ptr=ffff8800721a2f00 bytes_req=64 bytes_alloc=64 gfp_flags=GFP_KERNEL|GFP_ZERO

<idle>-0 [000] ..s3 18156.176053: kmalloc: call_site=ffffffff81619b36 ptr=ffff88006d554800 bytes_req=512 bytes_alloc=512 gfp_flags=GFP_ATOMIC

dropbear-1465 [000] ...1 18156.176257: kmalloc: call_site=ffffffff816650d4 ptr=ffff8800729c3000 bytes_req=2048 bytes_alloc=2048 gfp_flags=GFP_KERNEL

<idle>-0 [000] ..s3 18156.177717: kmalloc: call_site=ffffffff81619b36 ptr=ffff88006d555800 bytes_req=512 bytes_alloc=512 gfp_flags=GFP_ATOMIC

<idle>-0 [000] ..s3 18156.399229: kmalloc: call_site=ffffffff81619b36 ptr=ffff88006d555800 bytes_req=512 bytes_alloc=512 gfp_flags=GFP_ATOMIC

dropbear-1465 [000] ...1 18156.399434: kmalloc: call_site=ffffffff816650d4 ptr=ffff8800729c3000 bytes_http://rostedt.homelinux.com/kernelshark/req=2048 bytes_alloc=2048 gfp_flags=GFP_KERNEL

<idle>-0 [000] ..s3 18156.400660: kmalloc: call_site=ffffffff81619b36 ptr=ffff88006d554800 bytes_req=512 bytes_alloc=512 gfp_flags=GFP_ATOMIC

matchbox-termin-1361 [001] ...1 18156.552800: kmalloc: call_site=ffffffff81614050 ptr=ffff88006db34800 bytes_req=576 bytes_alloc=1024 gfp_flags=GFP_KERNEL|GFP_REPEAT

To again disable the kmalloc event, we need to send 0 to the enable file:

root@sugarbay:/sys/kernel/debug/tracing/events/kmem/kmalloc# echo 0 > enable

You can enable any number of events or complete subsystems (by

using the enable file in the subsystem directory) and get an

arbitrarily fine-grained idea of what’s going on in the system by

enabling as many of the appropriate tracepoints as applicable.

Several tools described in this How-to do just that, including

trace-cmd and KernelShark in the next section.

3.2.4 trace-cmd / KernelShark

trace-cmd is essentially an extensive command-line “wrapper” interface

that hides the details of all the individual files in

/sys/kernel/debug/tracing, allowing users to specify specific particular

events within the /sys/kernel/debug/tracing/events/ subdirectory and to

collect traces and avoid having to deal with those details directly.

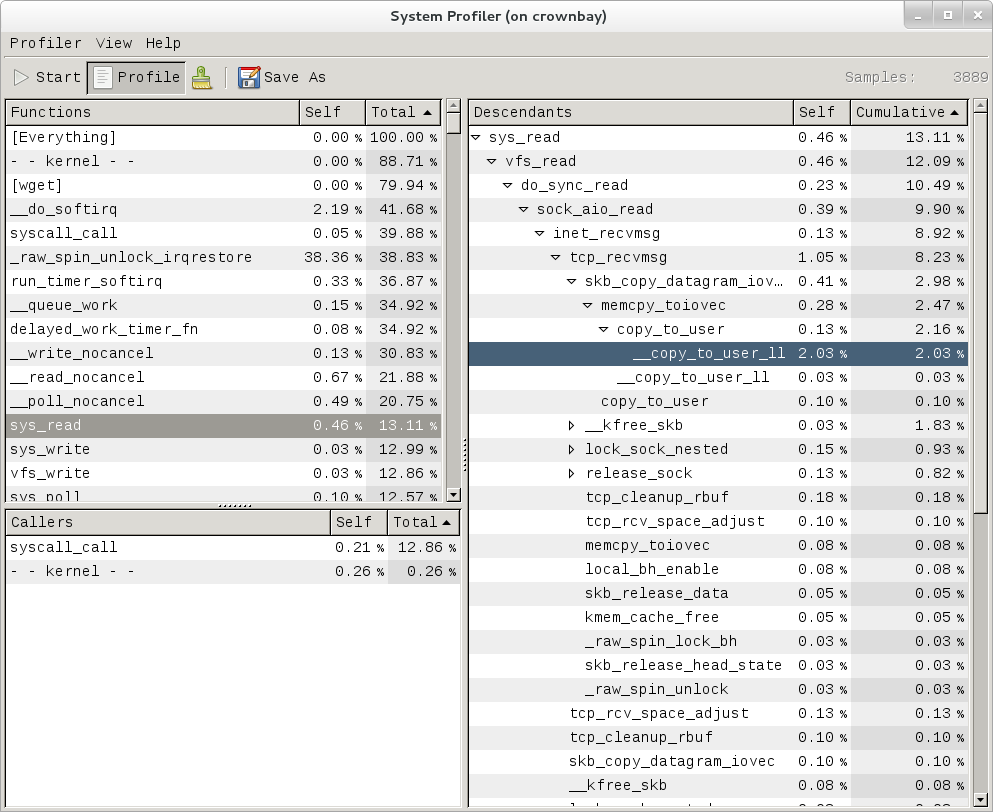

As yet another layer on top of that, KernelShark provides a GUI that allows users to start and stop traces and specify sets of events using an intuitive interface, and view the output as both trace events and as a per-CPU graphical display. It directly uses trace-cmd as the plumbing that accomplishes all that underneath the covers (and actually displays the trace-cmd command it uses, as we’ll see).

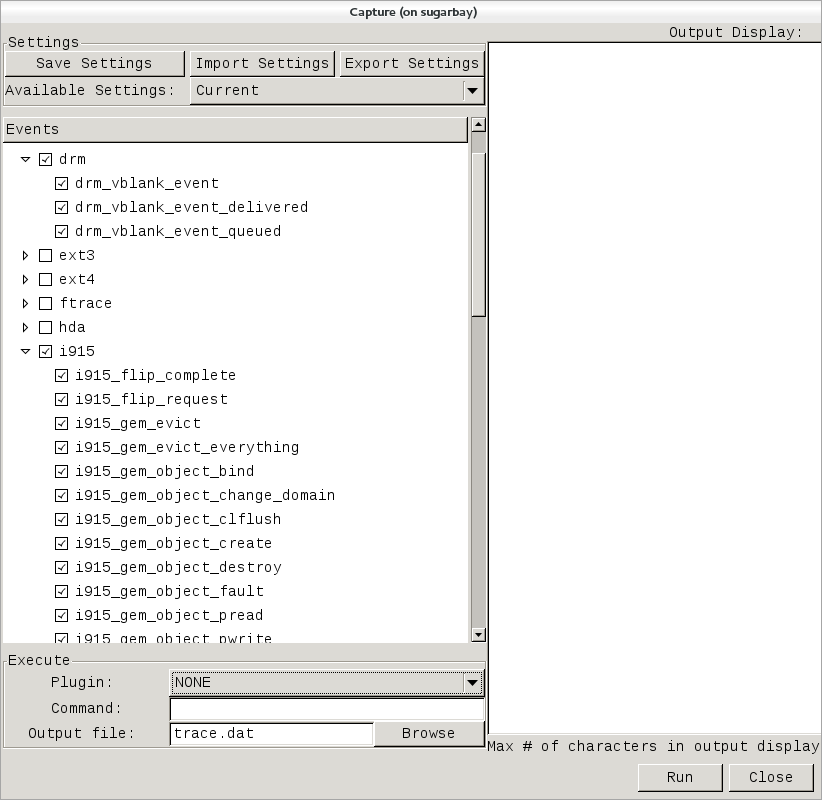

To start a trace using KernelShark, first start this tool:

root@sugarbay:~# kernelshark

Then open up the Capture dialog by choosing from the KernelShark menu:

Capture | Record

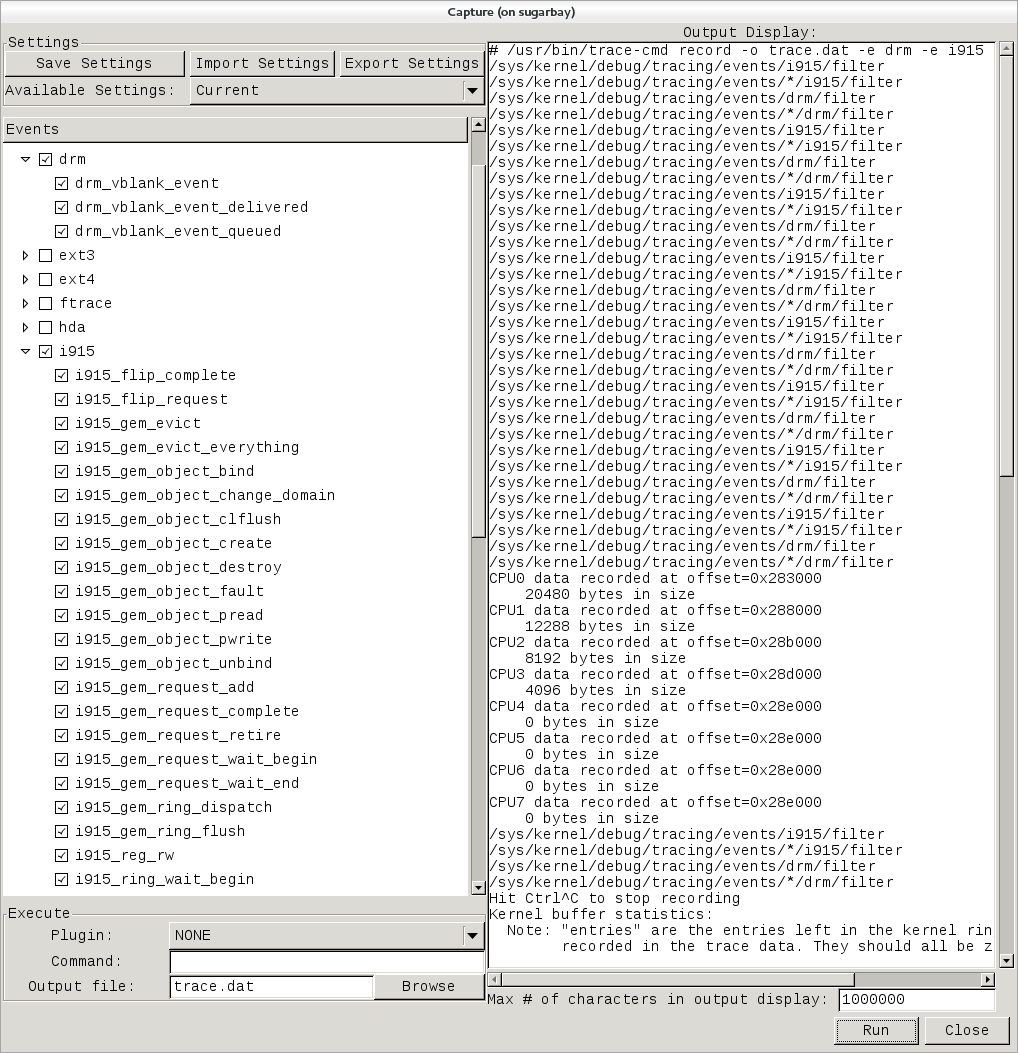

That will display the following dialog, which allows you to choose one or more events (or even entire subsystems) to trace:

Note that these are exactly the same sets of events described in the previous trace events subsystem section, and in fact is where trace-cmd gets them for KernelShark.

In the above screenshot, we’ve decided to explore the graphics subsystem

a bit and so have chosen to trace all the tracepoints contained within

the i915 and drm subsystems.

After doing that, we can start and stop the trace using the Run and

Stop button on the lower right corner of the dialog (the same button

will turn into the ‘Stop’ button after the trace has started):

Notice that the right pane shows the exact trace-cmd command-line that’s used to run the trace, along with the results of the trace-cmd run.

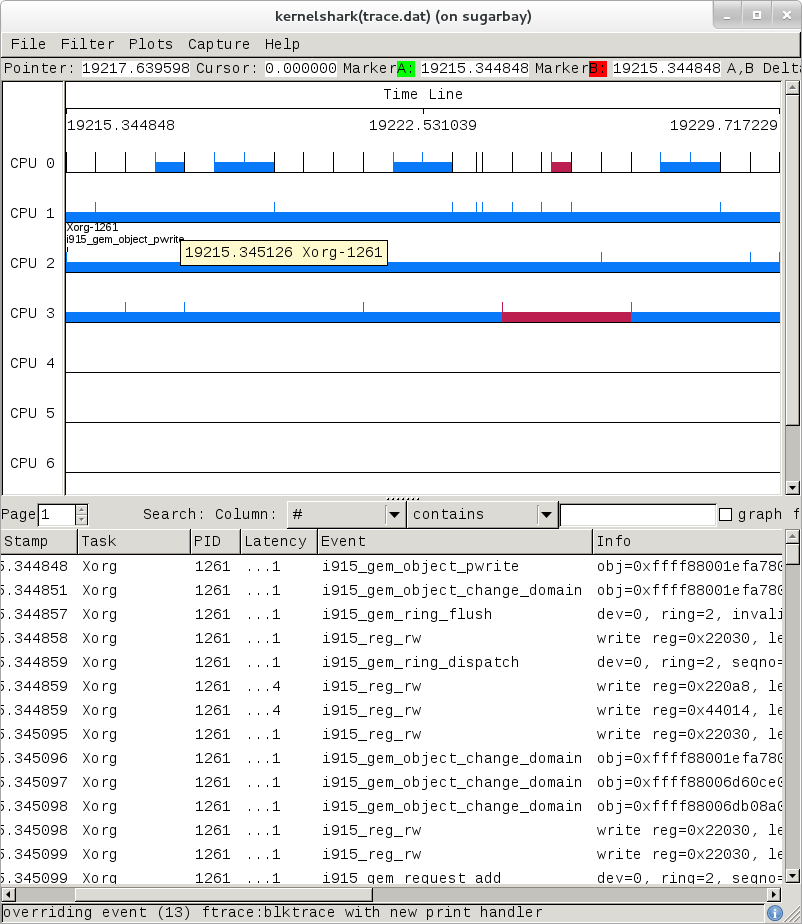

Once the Stop button is pressed, the graphical view magically fills up

with a colorful per-CPU display of the trace data, along with the

detailed event listing below that:

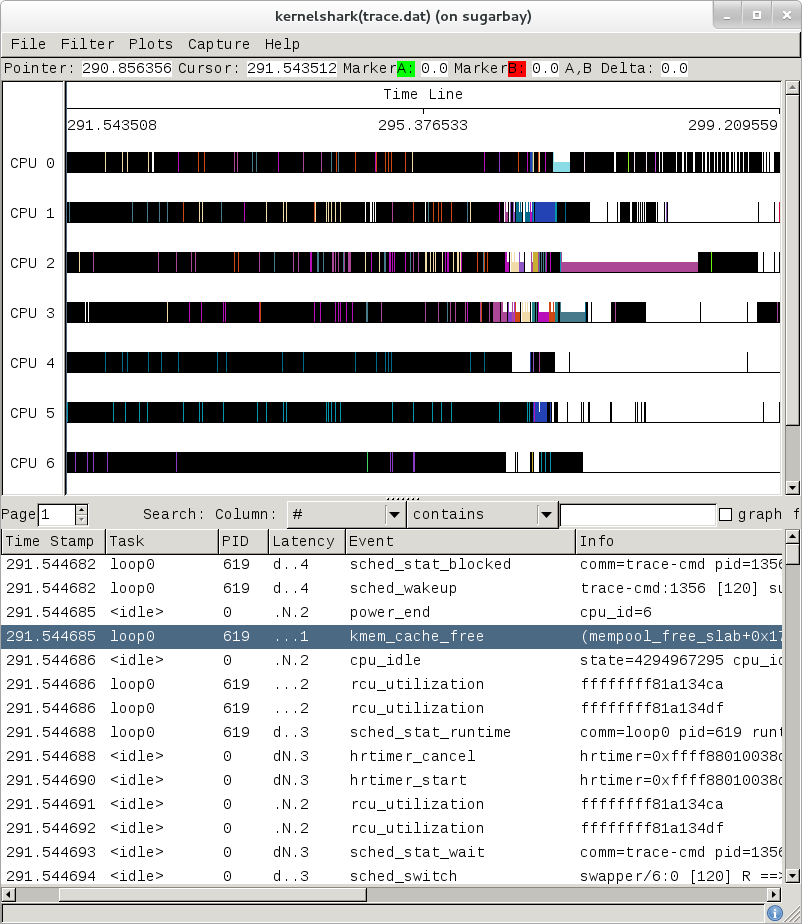

Here’s another example, this time a display resulting from tracing all

events:

The tool is pretty self-explanatory, but for more detailed information on navigating through the data, see the KernelShark website.

3.2.5 ftrace Documentation

The documentation for ftrace can be found in the kernel Documentation directory:

Documentation/trace/ftrace.txt

The documentation for the trace event subsystem can also be found in the kernel Documentation directory:

Documentation/trace/events.txt

A nice series of articles on using ftrace and trace-cmd are available at LWN:

See also KernelShark’s documentation for further usage details.

An amusing yet useful README (a tracing mini-How-to) can be found in

/sys/kernel/debug/tracing/README.

3.3 SystemTap

SystemTap is a system-wide script-based tracing and profiling tool.

SystemTap scripts are C-like programs that are executed in the kernel to gather / print / aggregate data extracted from the context they end up being called under.

For example, this probe from the SystemTap

tutorial just prints a

line every time any process on the system runs open() on a file. For each line,

it prints the executable name of the program that opened the file, along

with its PID, and the name of the file it opened (or tried to open), which it

extracts from the argument string (argstr) of the open system call.

probe syscall.open

{

printf ("%s(%d) open (%s)\n", execname(), pid(), argstr)

}

probe timer.ms(4000) # after 4 seconds

{

exit ()

}

Normally, to execute this

probe, you’d just install SystemTap on the system you want to probe,

and directly run the probe on that system e.g. assuming the name of the

file containing the above text is trace_open.stp:

# stap trace_open.stp

What SystemTap does under the covers to run this probe is 1) parse and convert the probe to an equivalent “C” form, 2) compile the “C” form into a kernel module, 3) insert the module into the kernel, which arms it, and 4) collect the data generated by the probe and display it to the user.

In order to accomplish steps 1 and 2, the stap program needs access to

the kernel build system that produced the kernel that the probed system

is running. In the case of a typical embedded system (the “target”), the

kernel build system unfortunately isn’t typically part of the image

running on the target. It is normally available on the “host” system

that produced the target image however; in such cases, steps 1 and 2 are

executed on the host system, and steps 3 and 4 are executed on the